Historically, marriage and family therapists (MFTs) have not been contracted or hired by school districts to provide therapeutic services to children (Cooper-Haber & Haber, 2015). However, in 2018, approximately 3.5 million adolescents received mental health services in education settings (U.S. Department of Education, 2021). Of those 3.5 million receiving services, adolescents from low-income households, public insurance, and ethnic minorities were more likely to only access school-based services (Ali et al., 2019). These numbers have been on the incline since the COVID-19 pandemic (U.S. Department of Education, 2021) and have posed a unique situation for MFTs to lend their systemic skills to children, their families, and the schools for which they attend.

As systemic thinkers, MFTs can contribute to a comprehensive approach to student support. By addressing the interplay between family dynamics, school environment, and the student’s individual needs, MFTs can help create a holistic support system for students. This includes promoting positive parent-school partnerships, addressing family conflicts that may impact the student’s functioning, and collaborating with teachers and administrators to implement strategies that enhance the student’s academic and emotional development. MFTs are the only mental health professionals required to receive training in family therapy and family systems.

The American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy (AAMFT) advocates for MFTs to be included The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) passed in 2015, which replaced the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) initiative (U.S. Surgeon General, 2015). ESSA mandates every state to measure reading, math, and science performance. MFTs can utilize their unique skills to help these children and their families. We must be prepared to work in schools. To do so, MFTs will have to learn how to speak the language of schools, collaborate with school personnel, educate others on our role, and advocate for the MFT profession (Vennum & Vennum, 2013). The following will provide a short background on the current state of MFTs in schools and cover the school vocabulary and process for identifying students for special education. It will also cover the potential roles of MFTs and how they can contribute to the mental health team. Finally, ideas for advocating on the local, state, and national levels will be provided.

NCLB-ESSA and its impact on MFTs

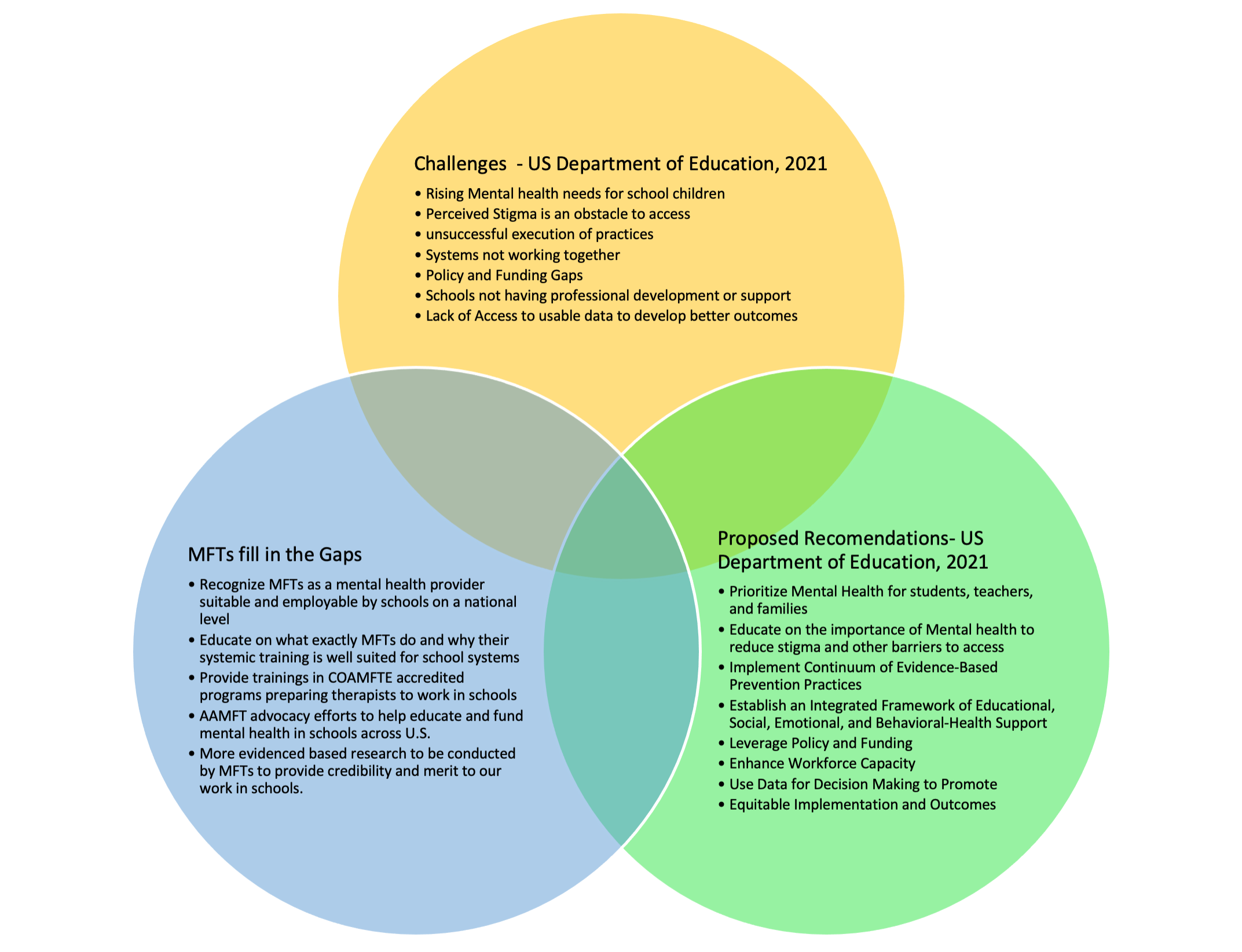

Figure 1. Current state of MFTs in Schools, U.S. Department of Education 2021

To fully understand the school culture, it is crucial to understand the federal laws in place and the history behind MFTs being left out of the schools. In 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was passed granting federal and state involvement in children’s education. One of its components was to promote systemic practices to ensure that all students including those with academic, developmental, behavioral, or emotional needs receive adequate support (No Child Left Behind, 2001). While MFTs are recognized as one of the five core mental health disciplines recognized by the Health Resources and Services Administration (42 CFR Part 5, App. C), they were excluded from the NCLB Federal Law preventing MFTs from accessing the six million children and adolescents with serious emotional disturbances in school (U.S. Surgeon General, 2015). In 2015, the NCLB Act was replaced by The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) which, unfortunately, still does not recognize MFTs as mental health professionals who can provide school-based services. While the ESSA acknowledges the connection between students’ mental and behavioral health wellness and positive student achievement, school climate, graduation rates, and the ability to function within the community (U.S. Department of Education, 2021), the exclusion of MFTs limits the resources and expertise available to support students in need. ESSA relies heavily on the states to mandate the protocol for which they choose to provide mental health services in their schools. This is where AAMFT on a local, state, and national level can advocate for MFTs to be recognized in school districts thus providing treatment that has been proven highly effective with school children (U.S. Surgeon General, 2015).

The importance of school vocabulary and special education vocabulary

School systems and even individual school buildings are unique settings with their own culture and protocols which include their own vocabulary. As mental health providers, MFTs are well-versed in the acronyms of their field. For example, abbreviations such as GAD (Generalized Anxiety Disorder), IOP (Intensive Outpatient Services), or AOD (Alcohol and Other Drugs) are used frequently by mental health professionals. Much like the mental health field, schools also have their own set of acronyms, so one must be fluent in them to be successful in the school system.

Working within the educational system requires familiarity with the language and processes used to identify and support students with special needs. MFTs can benefit from understanding key terms related to special education, such as the Individualized Education Plan (IEP), Section 504, and Response to Intervention (RTI). Collaborating with school personnel and demonstrating knowledge of these terms can facilitate effective communication and collaboration.

Figure 2. School Vocabulary

School personnel are not able to make mental health diagnoses. However, they do have a process for identifying students who need assistance. Identifying students for special education services such as an IEP is a several-step process that is directed by the IDEA (IDEA, 2023). This federal law governs every step of the process. Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) may be referred to as an Intervention Assistance Team (IAT), a Response to Interventions Team, a Behavior Academic Assistance Team, or another district-specific designation. This team consists of district staff members (Special Education teacher, Speech Language Pathologist, School Psychologist, School Counselor, Social Worker, or OT/PT if needed, the child’s parents, and the child (as appropriate) and may include other individuals who have specific knowledge about the child. The team, through collaboration, develops intervention strategies to support the student’s success in the classroom. As one can see, there are many different abbreviations/acronyms for many common processes in schools.

- Initial Meeting: When a student is struggling academically or behaviorally, a meeting is held with parents, teachers, and relevant professionals to discuss concerns and determine if a disability evaluation is needed.

- Response to Intervention (RTI): Schools may implement a multi-tiered system of support, such as RTI, to provide targeted interventions and monitor a student’s progress before initiating a formal evaluation.

- Multifactor Evaluation (MFE): If a student’s difficulties persist despite interventions, a comprehensive evaluation is conducted, considering various factors, such as academic performance, behavior, and health history.

- Evaluation Team Report (ETR): The ETR summarizes assessment results, including findings related to a disability, and serves as the basis for determining eligibility for special education and related services.

- Individualized Education Program (IEP): Once a student is found eligible, an IEP is developed, outlining specific goals, accommodations, and services tailored to meet the student’s unique needs.

- The student may not qualify for Special Education services and the team may decide to write a 504 Plan.

Differences between an IEP and a 504 plan

There are great differences between an IEP and a 504 plan (Ohio Legal Help, 2023). An IEP and a 504 Plan are both legal documents designed to support students with disabilities in educational settings. An IEP is a legally binding document for students who meet the eligibility criteria in one of the 13 categories listed below. It is a comprehensive plan that includes specific goals, objectives, and services tailored to meet the unique educational needs of the student. It is a legally enforceable document that outlines the rights and protections afforded to the student and their family. The 504 Plan on the other hand is derived from Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 which prohibits discrimination based on disability in programs receiving federal funding. It is a regular education initiative that provides accommodations and support for students with disabilities who do not meet the criteria for an IEP. For example, many students diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder may not qualify under the federal definitions for an IEP but may qualify for a 504 Plan. The 504 plan ensures that students have equal access to education by addressing barriers and providing necessary accommodations. In summary, the main difference between an IEP and a 504 plan lies in the eligibility criteria and the level of services provided. While an IEP is for students who require unique, specialized instruction, a 504 plan is for students who need accommodations and support but do not require specialized instruction. Students on a 504 plan will not be assigned to special education teachers, instead, the regular education teachers are responsible for implementing the plan. Both plans ensure that students with disabilities receive the appropriate support to access and succeed in their education.

(See The Basics of Special Education for further information.)

MFTs can be an important part of an intervention assistant and/or pupil services team. MFTs can be contributing members of this team as they can provide assessment and intervention services to students with behavioral or emotional problems. They can also work with families to develop and implement support plans. MFTs can also provide training and support to school staff on issues such as child development, family dynamics, and crisis intervention. Although federal law does not include language around MFTs in schools, many states have MFTs as approved providers in the schools.

Progress toward school inclusion

As stated earlier, MFTs possess unique skills and expertise that can significantly contribute to meeting the mental health needs of students within school environments. Recognizing the importance of a comprehensive approach to student well-being, several states have taken steps to allow MFTs to practice in schools. There are 3 primary avenues that MFTs can work in schools: 1. School certification (direct hire); 2. Hiring through an agency that then places clinicians in schools (collaborative relationships with agencies); and 3. Hiring through private practice contracting. Between all three, many states have MFTs working in schools (E. Cushing, personal communication, May 13, 2023). Although there is not a comprehensive list of states which allow MFTs in schools (R. Smith, personal communication, May 11, 2023), below is a sampling of several states that have some laws that allow MFTs to be providers in schools.

- California: California recognizes MFTs as qualified professionals to provide mental health services in school settings.

- Connecticut: Connecticut has established policies permitting MFTs to practice in schools and contribute to student mental health.

- Illinois: In Illinois, MFTs are granted the ability to practice in state schools under specific legislation.

- Iowa: Iowa has recognized MFTs as approved providers in school settings, allowing their participation in addressing students’ mental health needs.

- Kentucky: Kentucky permits MFTs to practice in schools, facilitating the integration of mental health services into the educational system.

- Louisiana: Louisiana acknowledges MFTs as qualified professionals authorized to provide mental health services within the school environment.

- Ohio: Ohio has implemented policies allowing MFTs to serve as approved providers in schools, supporting the comprehensive mental health support system for students.

The following states have also placed MFTs in schools through one of the three opportunities identified above: Alaska, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington State, and Wisconsin, as well as on Tribal lands and in schools located on or near military bases (through contracts with military service provider agencies (E. Cushing, personal communication, May 13, 2023).

Advocacy

Advocacy is vital for promoting the recognition and utilization of MFTs in schools. While there is an acknowledgment of needing MFTs in the schools, little has been done to bring this to fruition on a national level. Research has long since highlighted this as a growing and imperative need in the MFT field, yet little progress has been made that identifies MFTs as a superior choice in schools nationally. As stated above, several states (i.e., Connecticut, California, and Illinois), have successfully lobbied for state laws to allow MFTs to be approved providers in the schools supporting a comprehensive mental health support system for students. Advocacy efforts in other states should focus on identifying and educating stakeholders about the unique contributions of MFTs. This can include collaborating with professional organizations to influence policy changes and building partnerships with school administrators, policymakers, and legislators. MFTs can advocate for increased funding for mental health services in schools. They can also advocate for policies that support the integration of MFTs into the school system. Finally, MFTs can participate in local, state, and national advocacy campaigns.

Conclusion

The inclusion of MFTs in the educational setting is crucial for the well-being and success of students. As the number of students accessing mental health services in schools continues to rise, it is important to recognize the unique skills and perspectives that MFTs bring to the table. MFTs need to be prepared to enter the schools by being educated on the processes through which students will access their services. By understanding the history, advocating for policy changes, and demonstrating the value of their systemic approach, MFTs can play a vital role in promoting positive outcomes for students, families, and schools.

Further reading: Your middle school child is the most amazing person

MFTs can be an important part of an intervention assistant and/or pupil services team.

Rebecca Boyle, PhD, IMFT-S, PCC-S, Professional School Counselor, and AAMFT Professional Member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations, is a Core Professor in the School of Counseling at Walden University. She also works part-time for a pediatric practice as a behavioral health therapist seeing couples, families, and children. She conducts educational testing for those students who are struggling in the school setting. She is the past president of the Ohio Association for Marriage and Family Therapists. Her life’s work and passion have been to help students and their parents navigate the K-12 educational system. Boyle has worked with students from the K-PhD level and loves teaching new therapists how to work in the schools. She received her doctoral degree from the University of Akron in Counselor Education and Supervision with a focus on marriage and family therapy. Boyle worked at Akron for several years as a director of their training clinic where masters and doctoral students completed their practicum/internships in Akron’s state-of-the-art training clinic. She continues to supervise trainees as they work toward their licensure.

Molly McDowell-Burns PhD, IMFT-S, LPCC-S, RPT, AAMFT Professional Member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations, is the owner of Family Connection 9, LLC in Wadsworth, Ohio. She specializes in treating Borderline Personality Disorder from a systemic lens to address the complex needs and issues this population possesses. She emphasizes a relational component when treating BPD as she feels it is an essential part of the healing process. She also enjoys working with children/adolescents/teenagers to help them have more effective coping skills, stronger self-esteem, and better relationships with parents/guardians. McDowell-Burns received her doctoral degree at The University of Akron in Counselor Education and Supervision with a focus on marriage and family therapy and currently teaches Masters and Doctoral classes at National University. In addition to her clinical and academic aspirations, she supervises clinical trainees working towards licensure as part of her mission to help train and advance the profession of couple/marriage and family therapy.

Ali, M. M., West, K., Teich, J. L., Lynch, S., Mutter, R., & Dubenitz, J. (2019). Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. The Journal of School Health, 89(5), 393-401. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12753

Cooper-Haber, K., & Haber, R. (2015). Training family therapists for working in the schools. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37, 341-350.

IDEA. (2023). U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

No Child Left Behind. (2001). Congress.gov.

Ohio Legal Help. (2023). Special education for your child (2023). Retrieved from https://www.ohiolegalhelp.org/topic/special-education

U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Washington, DC: Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Supporting Child and Student Social, Emotional, Behavioral, and Mental Health Needs.

U.S. Surgeon General. (2015). AAMFT fact sheet. Retrieved from http://www.aamft.org/iMIS15/AAMFT/Content/Advocacy/Family_Therapists_in_Schools.aspx

Vennum, A., & Vennum, D. (2013). Expanding our reach: Marriage and family therapists in the public school system. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35(1), 41-58

Laundy, K. C., Nelson, W., & Abucewicz, D. (2011). Building collaborative mental health teams in schools through MFT school certification: Initial findings. Contemporary Family Therapy, 33(4), 384-399.

Other articles

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: The Evolution of Family Therapy in Schools

Since we began to achieve licensure in the US over 30 years ago, the profession of marriage and family therapy has grown in several areas. Five years ago, AAMFT created several topical interest groups to stimulate and track the growth of marriage and family practice in traditional mental health as well as new domains.

Kathleen Laundy, PsyD, Erin Cushing, MA & Anne Rambo, PhD

The Power of Coming “Out”: Creating Safe Spaces for Young People to be Themselves

Recently, I had the pleasure and privilege of a teenager coming out to me as gay. The process of this discovery was a long one. He disclosed to me that he had seen a movie, Call Me By Your Name, that he found arousing. We had a long conversation about sexuality and how it falls on a spectrum. I explained that most people’s sexualities are not “either, or” and that they fall on a line of multiplicity.

Gretchen Cooper, MA

Consensual Non-Monogamy and Attachment Styles

Marriage and family therapists (MFTs) have a unique skillset to manage complex relationships between client constellations, a skill which is essential for working with people in consensual non-monogamous relationships (CNMRs). With around 5% of the population in the U.S. being involved in a CNMR (Ka et al., 2022) and sexual minorities being more likely to engage in CNMR than heterosexuals (Moors et al. 2017), it is imperative that MFTs understand how attachment to multiple romantic partners can exist in healthy ways so as to best support this population.

Katherine M. Blasko, MS & Jakob F. Jensen, PhD