In my clinical practice, texting, social media, screen time, or gaming is identified as an issue for virtually all children, adolescents, and families with whom I work. I have learned to assess for screen time issues along with the old clinical standards, such as mood, academic performance, behavioral issues, sleep, and eating. However, I used to rely on less-than-professional resources about screen time, such as my online newsfeeds, webs searches, and my own life experience. So, when I had a chance to go on sabbatical at my university, I immediately knew how I wanted to update my knowledge: screen time for families.

I took a few months to review the research related to the effects of screen time on child and adolescent health and development (see www.screentimeforfamilies.net). In this article, I provide family therapists with an overview of the existing research along with evidence-informed guidelines they can share with their clients.

How screen time impacts children and adolescents

Research on screen time actually began in the 1970s with concerns related to children watching television (e.g., Anderson, Levin, & Pugzles Lorch, 1977). Over the past 20 years, there has been an increasing amount of research on video games, especially related to the newly recognized Gaming Disorder, by the World Health Organization (2018), and Internet Gaming Disorder appears in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) as a condition for further study. Youth having extensive access to the internet, social media, and digital devices is a relatively new phenomenon of the past decade, and thus there is less research on the impact of today’s screen use than one would hope. However, after decades of not funding a large-scale study on this topic, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (2019) is currently conducting an investigation related to youth health that includes screen time, but it will take another decade or more before we have long-term results. Most parents will be done raising their kids before we have a solid understanding of how today’s technology affects growing brains and bodies. Therefore, therapists and parents will have to work with the information we have available now, which is sufficient to make relatively specific and informed decisions in most areas. The existing evidence base addresses how screen time affects youth sleep, weight, aggression, attention, mental health, and neurological development.

Sleep

One of the strongest correlations between media use and youth behavior is related to sleep: the more children and teens have access to screens, the less they sleep. Sleep is critical for growing brains and for learning, and is an important part of consolidating memories, which is essential for academic success (Knell, Durand, Kohl, Wu, & Pettee Gabriel, 2019). However, only 63% of 15-year-olds in 2012 reported getting more than seven hours of sleep per night (Twenge, Krizan, & Hisler, 2017). Decreases in adolescent sleep have been directly associated with the increase in screen time and social media. For example, those with access to a portable device at night had a 79% chance of getting less than nine hours per night for adolescents, or 10 hours for children (Carter, Rees, Hale, Bhattacharjee, & Paradkar, 2016). The research also emphasizes that screen time an hour before bed is particularly detrimental because the screen’s blue light inhibits the production of melatonin, interfering with the body’s natural circadian rhythms and making it more difficult for children (and adults) to fall asleep (Bradford, 2016).

Weight management and obesity

The second-best established concern related to screen time is childhood obesity and weight management (Robinson et al., 2017). This research began with the study of television viewing and has continued with today’s mobile devices. However, the exact reason screen time use is correlated with obesity is unknown because the seemingly obvious “lack of exercise” hypothesis is not consistently supported by the evidence. Not all children who spend more time on screens actually get less exercise. Nonetheless, researchers have found that reducing screen time in adolescence has a significant impact on obesity in young adulthood (Boone, Gordon-Larsen, Adair, & Popkin, 2007). In their 2016 policy statement on media and youth, the American Academy of Pediatrics emphasized the importance of ensuring children and adolescents have at least one hour of moderate-intensity exercise in their schedule before allowing screen time to reduce the chances of obesity and weight-related issues.

Aggression and desensitization to violence

A topic of significant public debate, screen time, particularly violent video games and media, have been associated with increased aggression and decreased sensitivity to violence and the suffering of others. Studies from the 1960s established that children who watch violence are more likely to act violently (Kamenetz, 2018). Several studies have found that playing violent video games reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex and a person’s ability to regulate one’s mood and behavior; these effects are measurable not only immediately after playing, but also weeks later (Hummer, Kronenberger, Wang, & Mathews, 2019). Similarly, researchers have found that playing character-based, risk-glorifying video games increased delinquent behaviors in all areas measured, including alcohol use, smoking, aggression, and risky behavior (Hull, Brunelle, Prescott, & Sargent, 2014). However, experts are also quick to point out that violent games and media cannot and do not explain serious acts of violence, such as school shootings, which are correlated much more significantly with mental illness, dysfunctional family dynamics, and economic insecurity (Kamenetz, 2018). Furthermore, evidence indicates that certain children seem to be more vulnerable to the negative outcomes than others, although the moderating factors are not yet clearly identified. On a more hopeful note, Harrington and O’Connell (2016) found that playing prosocial video games results in increased prosocial behavior, such as empathy, sharing, and positive emotion.

Both social media and long video game sessions are correlated with higher rates of adolescent depression and anxiety.

Attention problems

Few dispute the claim that screen time affects children’s (and adult’s) attention spans. Both television viewing and video game playing have been found to decrease children’s, adolescents’, and young adults’ attention spans, so the impact extends far beyond the early years (Swing, Gentile, Anderson, & Walsh, 2010). Two different issues relate to attention and screen time: a) amount of time on screen and, b) speed of images on screen (Kamenetz, 2018). While the first is relatively obvious, the second is less so and more critical for younger children in particular. The faster images shift on screen, the more the stress response is triggered, with younger children having a more noticeable response. Thus, a video game such as solitaire that moves at a speed determined by the player has a very different effect on the nervous system than one such as Tetris or Bejeweled where the tempo of falling puzzle pieces is entirely controlled by the game itself. The more time spent watching fast moving images, the more the stress response is triggered and the more difficult it can be to pay attention to slower, normally paced activities, such as reading or playing a board game.

Depression, anxiety, and narcissism

The National Institute of Mental Health reports that the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder for adolescents 13-17 is 49.5% with the three most common disorders being attention deficit disorder (ADD), anxiety, and depression (Merikangas et al., 2010). Both social media and long video game sessions are correlated with higher rates of adolescent depression and anxiety (Kamenetz, 2018), and factors such as frequency of posting selfies, number of followers, and time spent on social media has been correlated with narcissism (McCain & Campbell, 2018). Although screen time is not causal of these disorders, increased screen time can be a sign that a child is struggling with one of these or another mental health disorder and intervening on the amount and type of screen time may help reduce symptoms.

Brain changes and academic performance

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (2019) is in the process of conducting a large-scale study examining, among other things, the long-term effects of screen time. The study is following over 11,000 children at 21 sites across the United States. Their initial data had some significant findings related to screen time and brain development:

- MRI scans found significant differences between the brains of some children (sample included 9-10 year olds) who reported over 7 hours per day of total screen time.

- Children who reported more than 2 hours per day of screen time had lower scores on language and reasoning tests.

These findings are particularly concerning since the average 5-7 year old has 4.5 hours per day and the average 8-12 year old has 6 hours per day.

Parenting around screen time is a complex issue, and therapists need to factor in numerous dynamics, such as family configuration, child temperament, parenting style, cultural and gender norms, and mental health issues. The following recommendations offer therapists a place to begin conceptualizing how best to begin dialogues and explore possibilities with families related to these issues. Ultimately, the goal is to help children develop a healthy relationship with screens, the internet, and their virtual social worlds, which parents do through mentoring, conversation, and role modeling.

The recommendations below are based on those from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP, 2016), combined with the emerging research findings described previously, and provide an initial framework for ongoing family dialogue about these multifaceted issues.

Infants and toddlers: 0-24 months

Although there are apps and videos targeting this age range, experts agree that no amount of screen time is recommended for children in the first two years with the exception of video chatting to connect with relatives (AAP, 2016). Researchers found that infants and toddlers who viewed media prior to 18 months had significant and measurable drops in language development (Zimmerman & Christakis, 2005). At age 18-24 months, parents can introduce high-quality (i.e., educational) shows that the parents sit down and watch with the child.

Preschoolers: 2-5 years old

The AAP (2016) recommends a clear time limit for preschool-aged children: no more than one hour of total screen time (television, tablets, computers, and smartphones combined). The AAP recommends strongly that parents watch or play with the child to help the child understand and engage with the media. Co-viewing and co-playing enable parents to coach children on how to engage digital media in healthy ways and offer opportunities to strengthen the parent-child bond (Sanders, Parent, Forehand, & Breslend, 2016).

Elementary school aged children: Ages 6-12

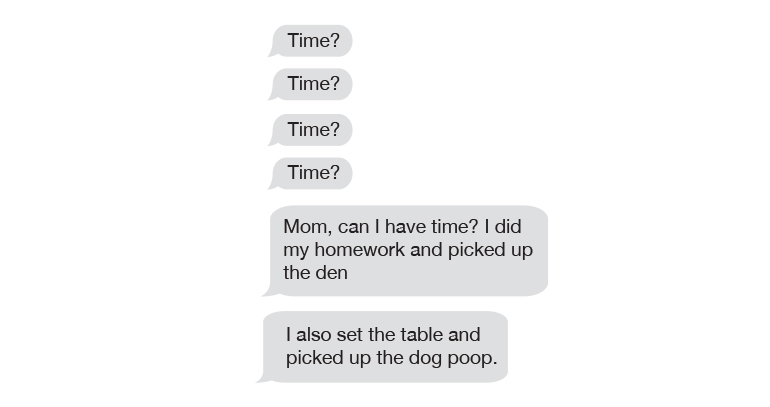

At this age, parents need to monitor, manage, and observe the impact of screen time on each child and adjust as needed, but with an overall attitude of developing a lifetime of healthy digital habits. Setting healthy limits and creating healthy attitudes towards screen time in these early years sets a solid foundation for effectively managing it themselves in adolescence and adulthood. The easiest system for managing time is to use not only the built-in parental controls in virtually all digital devices, but also employ third-party parenting control apps that allow parents to schedule and control screen time remotely (however, note that you will receive texts like the ones at the beginning of this article regularly). As noted previously, screen time should never come before a minimum of an hour of daily exercise and a full night’s sleep (10-11 hours at this age). Smart phones and social media are not advised at this age, and parents should carefully research the ratings and content of apps and games before purchase. Ideally, parents play with their children to better understand how a particular game or show may be affecting them. Finally, parents should regularly have discussions and conversations about screen time and media with children throughout these years to help them develop good habits and attitudes.

Middle and high school aged youth: Ages 12-18

Parents need to change their management strategies in middle and high school because the focus quickly shifts to online safety—use built-in parental controls that provide a baseline of filtering inappropriate content and location tracking, a third-party app that allows parents to monitor online activities, including contacts, internet search terms, websites visited, time in each app, texting patterns, etc. Such apps typically allow adolescents to use an allowance of time as they choose throughout the day to develop self-monitoring skills, which differs from apps that require parents to set predetermined periods of time for younger children. Because the National Sleep Foundation (2019) estimates that less than 15% of teens typically get the recommended 9-10 hours of sleep per night, parents are strongly encouraged to collect all digital devices (or use an app to disallow use) one hour before a reasonable bedtime in addition to ensuring an hour of exercise per day.

During these years, perhaps the most difficult decisions parents have to make are related to allowing social media and violent games/media; the pros and cons of allowing such media must be considered for each individual child. Similarly, parents have the challenging task of addressing a wide variety of digital sexual issues, including internet pornography, sexting (texting sexually explicit photos and videos), online sexual predators, and sex trafficking. In addition to ongoing family discussions about these difficult topics, third-party parental control apps offer the most effective option for identifying these issues before they get out of hand. During adolescence, parents also need to monitor for mood and anxiety issues, which are often exacerbated with both increased screen time and specific types of content. Lastly, perhaps the most important task is to role model and openly discuss the many challenges and dilemmas of screen time, the internet, and living in our digital age. These frank conversations set the foundation for a healthy relationship with media for a lifetime, which is the ultimate goal.

Closing reflections

Marriage and family therapists are in a unique position to help families with children of all ages effectively navigate the many challenges of parenting in the digital age. Although we do not have simple and clear answers to all concerns, we have sufficient research to offer specific and meaningful guidance to parents who typically struggle with knowing how to effectively parent in this new frontier.

Diane R. Gehart, PhD, LMFT is an AAMFT Approved Supervisor and Clinical Fellow, and professor and COAMFTE program director at California State University, Northridge. She is author of Mindfulness for Chocolate Lovers: A Lighthearted Way to Stress Less and Savor More Each Day and Mastering Competencies in Family Therapy. She presents regularly at AAMFT conferences on related topics. Find her online www.dianegehart.com and www.screentimeforfamilies.net.

REFERENCES

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2016). Media and young minds: Policy statement. Pediatrics, 138(5) e20162591; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-2591

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Arlington, VA: Author.

Anderson, D. R., Levin, S. R., & Pugzles Lorch, E. (1977). The effects of TV program pacing on the behavior of preschool children. AV Communication Review, 25(2), 159-166.

Boone, J. E., Gordon-Larsen, P., Adair, L. S., & Popkin, B. M. (2007). Screen time and physical activity during adolescence: Longitudinal effects on obesity in young adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 4(26).

Bradford, A. (2016). How blue LEDs affect sleep. Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/53874-blue-light-sleep.html

Carter, B., Rees, P., Hale, L., Bhattacharjee, D., & Paradkar, M. S. (2016). Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 1202-1208.

Harrington, B., & O’Connell, M. (2016). Video games as virtual teachers: Prosocial video game use by children and adolescents from different socioeconomic groups is associated with increased empathy and prosocial behaviour. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 650-658.

Hull, J. G., Brunelle, T. J., Prescott, A. T., & Sargent, J. D. (2014). A longitudinal study of risk-glorifying video games and behavioral deviance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(2), 300-325.

Hummer, T. A., Kronenberger, W. G., Wang, Y., & Mathews, V. P. (2019). Decreased prefrontal activity during a cognitive inhibition task following violent video game play: A multi-week randomized trial. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8(1), 63-75.

Kamenetz, A. (2018). The art of screen time: How your family can balance digital media and real life. New York: Public Affairs.

Knell, G., Durand, C. P., Kohl, H. W., Wu, I. H. C., & Pettee Gabriel, K. (2019). Prevalence and likelihood of meeting sleep, physical activity, and screen-time guidelines among US youth. JAMA Pediatrics, DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4847

McCain, J. L., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Narcissism and social media use: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 7(3), 308-327.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980-989.

National Sleep Foundation. (2019). Teens and sleep. Retreived from https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/teens-and-sleep

Robinson, T. N., Banda, J. A., Hale, L., Lu, A. S., Fleming-Milici, F., Calvert, S. L., & Wartella, E. (2017). Screen media exposure and obesity in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 140(Suppl 2), S97-S101. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1758K

Sanders, W., Parent, J., Forehand, R., & Breslend, N. L. (2016). The roles of general and technology-related parenting in managing youth screen time. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(5), 641-646.

Swing, E. L., Gentile, D. A., Anderson, C. A., & Walsh, D. A. (2010). Television and video game exposure and the development of attention problems. Pediatrics, 126, 213-21.

Twenge, J. M., Krizan, Z., & Hisler, G. (2017). Decreases in self-reported sleep duration among US adolescents 2009-2015 and association with new media screen time. Sleep Medicine, 39, 47-53.

U. S. National Institutes of Health. (2019). The adolescent brain cognitive development study. Retrieved from www.abcdstudy.org

World Health Organization. (2018). Gaming disorder. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en

Zimmerman, F. J., & Christakis, D. A. (2005). Children’s television viewing and cognitive outcomes: A longitudinal analysis of national data. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(7), 619-625.

Other articles

The Social Media Battle Ground

With so many teens heavily connected to social media, it is vitally important to help parents understand the nuances of the positive and negative impacts of their children’s experiences in the digital world.

Katharine Larson, MA

Divorce, Remarriage, and Blended Families: Checklists for Therapists

Significant life transitions bring stressors to every member of the family. Systemic therapists are at the forefront of guiding families through divorce, co-parenting, and blending new families.

Neelia Pettaway, MC

Supporting Clients Facing Infertility

Couples dealing with infertility can benefit from unique support and understanding. Therapists should be familiar with infertility terminology, interventions, and the physical and emotional challenges couples face in their struggle to become parents.

Linda Meier Abdelsayed, MA