A note from the authors:

Before the ink had dried on our team’s previous piece in the March/April issue of Family Therapy Magazine (Family Evacuation after the Collapse of Afghanistan: 100,000+ Stories Yet to be Told; Charlés & Lewis, 2022), Russian forces had invaded the sovereign nation of Ukraine. When we first proposed this series, we had envisioned it as a set of articles (of which this piece is the second) about systemic work that is responsive to global events. We believe systemic practitioners have a great deal to contribute to the global community. Yet, writing about tumultous international events as they are happening in real time is not without risk. How to put words to events that defy capture in words? Fortunately, the history and the expertise of family therapy practice, and the role of systems thinking that informs it, is an important reminder of “the patterns that connect.” Patterns have meaning beyond their content; connections, too, can be drawn across many seemingly unconnected events. In this piece, our initial focus is on Ukraine. However, we hope this piece also invites readers to consider the role of systemic and context tools across multiple emergencies that are happening across the globe.

Ukraine: When war is the social determinant of health

The forced migration of millions of Ukrainians due to the Russian invasion is set to become the largest refugee crisis in Europe in this century. As of this writing, the numbers are stark: 150,000 fleeing daily, 6,250 every hour, 104 every minute, and 2 every second (Dillon, 2022). The dramatic and rapid influx of refugees into multiple countries mandates planning and preparation grounded in a human rights framework. It also benefits from systemic appreciation of the needs of families affected by war and conflict.

As family systems clinicians know very well, refugees and displaced persons present with complex public health and mental health needs, stemming precisely from the conditions by which they were forced to leave their homes. These conditions can include, but are certainly not limited to: Exposure to harm and risk of violence or death; disruption of social and familial networks and relationships; grief and ambiguous losses; abandonment of possessions and belongings; and living in unsafe or unsanitary conditions during the flight from home. In addition to these stark realities, we also know that 90% of those leaving Ukraine are women and children (UNHCR, 2022). From previous emergencies, we further know that depression and anxiety double on top of whatever needs may be psychosocially present for a population (Charlson et al., 2019). The European Union is responding to some of the complexity of the Ukrainian displacement by ensuring that Ukrainians entering EU nations have work, a year-long visa, education access, and language support. This response is an example of public policy following the science, with regard to mitigating risk and adapting to social and environmental shifts, and is in direct contrast to the EU response to the 2015 refugee crisis. Such a systemic, coherently coordinated response is one way the EU is attempting to limit the severe outcomes that can come from the many terrible impacts brought by war. Addressing them directly is also an investment in the future.

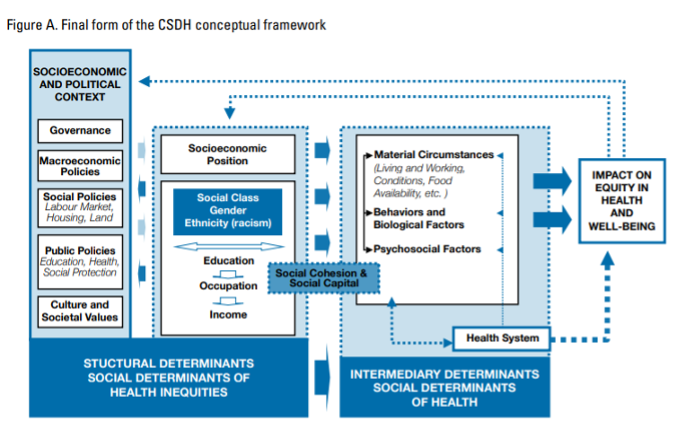

The social determinants of health (SdoH) refer to “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” (World Health Organization, 2022). When war is the social determinant of health, and the conditions as noted above include the products and process of war and ongoing armed combat, the conditions are indeed dramatic, but no less critical to assess. Informed social inquiry about “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” is relevant in war and in peace; it is always a matter that shapes mental health and well-being, everywhere, and is applicable to any geopolitical space on the globe. Family therapists know this concept perhaps more fittingly by one word: Context.

SDoH Framework: Conceptual Framework from WHO’s Commission on SDoH, which serves as a map for understanding non-medical factors contributing to health outcomes. Source: Solar & Irwin (2010).

Harare: “You cannot socially distance in a kombi”

In a recent visit to Zimbabwe, my (Dorcas’) native home country, the first disparity as social determinant of health that stood out to me was transportation.[1] Those from lower socioeconomic status, who need to work despite a pandemic, ride the crowded vans known as kombies. One cannot be socially distant in a kombi. A second and most concerning social determinant of health was the piles of trash I saw scattered throughout Harare. Driving through some of the low density (LDA) neighborhoods, I was welcomed by immaculate lawns and picture-perfect residences, as if looking at homes in a van Gogh painting. In neighborhoods such as Mbare, one of the high density neighborhood (HDA), crime-ridden areas in Harare, I saw endless piles of trash, plastic, and other recyclable waste. Imagine the toll on one’s mental health to see these images of trash on a daily basis. What does this say about how much one’s life and overall well-being is valued? What is the difference when compared to the life (and life expectancy) of those driving out of their van Gogh suburbs?

According to Makombe (2021), Zimbabwe experienced its worst cholera outbreak between 2008-2009, resulting in a death toll of 4,276, as reported by WHO. In fact, this was believed to be the worst outbreak on record in Africa (Youde, 2010 as cited in Makombe, 2021). The outbreak occurred primarily in these HDAs where inadequate water supply and sanitation concerns are constant. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the Zimbabwe government, like other governments around the world, imposed strict curfews. However, many of the curfew violations were found in these same HDA regions where people were lined up to purchase food or obtain water. When questioned about their willingness to break curfew, the response was, “kusiri kufa ndekupi,” (Makombe, 2021, p.284), which translates as “either way you are dead.” For these and other marginalized communities, being at the bottom of the totem pole is the norm and the piles of trash only serve as a reminder of this fact.

Zimbabwe is my (Dorcas) native country; however, the U.S. is also my home. In the U.S., a fitting example for me is the difference in life expectancy for residents in Streeterville, Illinois and Englewood, Illinois (Schencker, 2019). A resident from the affluent Streeterville neighborhood can expect to live to age 90, while a resident from Englewood, roughly 10 miles away, can expect to live to age 60, for similar reasons as exist in Harare. No country is exempt from the type of disparities between peoples’ daily activities of living, which I witnessed on my recent trip home. And one need not travel to find disparities; in times where we are seeing such deep inequality across the globe, the conditions that increase health disparities are accordingly evident in multiple ways.

Understanding and evaluating the process of behavioral health integration is a powerful way to improve SDOH for refugees. Because integration “is a fluid, multilayered, complex, and contested concept (Ali, Zendo, & Somer, 2021, p.1), the application of a model such as Hynie et al.’s (2019) Holistic Integration Model (HIM) may be useful. This model, which was an expansion of the Anger and Strang model of integration, highlights the sociopolitical context as well as the importance of social and structural process in the refugee resettlement process (Hynie et al., 2019). The HIM model additionally and critically emphasizes that responsibility for the adjustment process for refugees should also fall on the dominant host society. The HIM framework examines the social identity, personal history, and socioeconomic factors. The social identity framework of the model includes social connections, welcoming community, and institutional adaptation. The personal history framework includes language, culture, and functional; stated another way, assessing how refugees function in a new community given language and cultural differences. The socioeconomic context, which is subjective, centers around the individual’s sense of belonging and feelings of safety and security.

The Russian forces’ invasion of Ukraine, and indeed, all armed conflict and its sequelae, obligate us to examine global healthcare challenges with a social justice mindset and human rights framework. The systemic lens is a critical addition. It helps us recognize that what is happening in Harare, in Lviv, or in Englewood, Illinois, is about something bigger, something which affects all of us. An applied systemic lens is useful for advocacy across disciplines; using it effectively can bring meaning and commitment to change across multiple audiences. The social determinants of health are a tool by which we can apply our systemic methods and social justice lens, to more precisely clarify families’ needs and our responses, and work effectively and sustainably in the direction of enhancing psychosocial well-being. This too, is a global investment in the future that affects all of us.

Learning from past challenges related to refugee crises is another approach to providing effective services for refugees. Between 2018 and 2019, Australia received over 18,750 refugees leaving room for an additional 12,000 for Syrian refugees. In their study of 1180 adults (773 Iraqi and 407 Afghani) over age 18 (Thomasi et al., 2022), questionnaires translated into 14 languages included measures such as professional help-seeking, socio-demographic characteristics, general health, mental health, exposure to traumatic events, structural barriers (financial hardship), acculturation, discrimination, and trust. Findings revealed significant differences between the two ethnic populations, with poorer overall health and structural barriers predicting professional help-seeking. Older Afghan adults with high psychological distress were more likely to seek help, did not require interpreters, and knew how to find help online. For the Iraqi group, poor overall health and knowing how to find services were associated with a greater likelihood of help-seeking, while fewer financial hardships decreased the likelihood of seeking help. The study reiterated the need to tailor services to the specific needs of the population.

SdoH: What we know, what we don’t know, and what we need to know[2]

In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO), through the Alma-Ata Declaration, established a goal of Health for All. Fast forward to 2022, and this goal remains elusive. In wartime and in peacetime, the framework of the Social Determinants of Health can help us see the what of social conditions, and command us to ask informed questions about their why. How is it that the conditions among certain groups, or certain countries, or certain groups in certain countries, seem to defy an improvement in the SDOH “conditions”? If, as Solar and Irwin (2010) assert, the “the framing of social justice and health equity points towards the adoption of related human rights frameworks as vehicles for enabling the realization of health equity, wherein the state is the primary responsible duty bearer” (p. 4), what does that mean for the everyday practice of the systemic family therapist? How can we better appreciate the role of state responsibility and its obligations to well-being of her citizens, itself a part of international human rights law? If I am an advocate for family systems work, in policy circles near or far, what science can I draw from to help me speak to the moral value of supporting families’ well-being by reducing the risk of social conditions that challenge it?

For systemic family therapists—whether working in Zimbabwe, Europe or the US—system-wide advocacy—whether with clients in the therapy room or stakeholders outside of it—that inclusively and robustly addresses some of these knowledge/s can help us to analyze, design, and implement the public mental health policies and resources that families need for their health and well-being. Family systems practitioners’ expertise in relational process and its training, teaching, and implementation is a critical value much needed at the international table. This type of work requires collaborative, integrative care, and community and stakeholder engagement. Family therapists are experts in undertaking this daunting task of meaning-making with multiple systems, for the benefit of the families we serve.

Working in the direction of the future: Recommendations to address SDoH

Solar and Irvin (2010) presented three approaches to reducing health disparities: 1) Target projects for marginalized populations, 2) Closing the gap between the “worse-off” and “better-off” groups, and 3) Examining the social health gradient worldwide. These authors recommend the following strategies to address structural and intermediary determinants: 1) Policies on stratification; 2) Policies to reduce exposures of marginalized groups to health-damaging factors; Policies to decrease vulnerabilities of disempowered groups; and 4) Policies to reduce inequalities in health outcomes in social, economic, and health terms. Further, Caron and Adegboye (2021) propose a systemic approach to establishing Health for All: 1) assessing the health status and needs of populations, 2) developing policies to protect public health, and 3) assuring that necessary services are available.

The World Health Organization’s Council on the Economics of Health for All proposed the following foundational values:

- Valuing planetary health

- Valuing the diverse social foundations and activities that promote equity

- Valuing human health and wellbeing

Valuing planetary health requires an awareness and acknowledgement of the extent to which we are all affected by global issues outlined in the work of the United Nations: climate change, peace and security, poverty, racism, oppression, democracy, and human rights. Family therapists who understand that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” recognize the value of assessing every individual and family beyond the symptoms but to include an understanding of the impact of global issues on mental health.

Given that untreated relational issues can have momentous consequences on health, economy, and community (Hert et al., 2011; Insel, 2008, as cited in Bischoff et al, 2017), the systemic perspective from which many family therapy clinicians are trained can help to explain and understand the health disparity issues in the ecosystemic context of family and community functioning (Gehart, 2012; Lucksted et al., 2012 as cited in Bischoff et al., 2017). Family therapists play a powerful role in that they look beyond the individual to examine the “harmony and balance” of an individual’s “relationship system” (Kerr & Bowen, 1988, p. 56). The SdoH compel us to critically examine the needs of families and communities, whether they are Ukrainian refugees fleeing an invasion, or families using kombis to get to work despite the risk to their health during a pandemic in Harare. A recognition that SdoH on a local scale are also global issues that impede the quality of life for all is a step in the right direction towards response and recovery that can enhance health outcomes. Put another way, understanding social determinants of health is also a way to address, and implement, preventative measures that can reduce “ill-health,” across multiple contexts and on behalf of all of us, for the future.

[1] I (DM) write this from a position of privilege, fully cognizant of the fact that I immersed myself in Zimbabwean life for as long as I chose, and returned to the 24-hour benefits of life in the US where I reside.

[2] With gratitude to Karen Wampler.

Dorcas Matowe, PhD, is a licensed marriage and family therapist in the states of Florida and Illinois and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. She is a clinical lecturer at The Family Institute at Northwestern University and an adjunct professor at Nova Southeastern University’s Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice. She has worked and volunteered in mental health and social services with multicultural populations, particularly those from marginalized communities and served as a Board Member for the Broward Association for Marriage and Family Therapy in Florida. As a two-time recipient of AAMFT’s Minority Fellowship Award, her research focused on the prevalence of racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States. Her most recent publication was a chapter, “To Thine Own Self Be True” (2023) in A. G. James and L. A. Anderson’s (Eds.) Letters to a Young Practitioner: Essays of Advice (pp. 63-68). She continues to address racial and ethnic disparities and SDoH, primarily among the underserved, women of color, and children in the US and Zimbabwe through various projects and presentations.

Dorcas Matowe, PhD, is a licensed marriage and family therapist in the states of Florida and Illinois and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. She is a clinical lecturer at The Family Institute at Northwestern University and an adjunct professor at Nova Southeastern University’s Abraham S. Fischler College of Education and School of Criminal Justice. She has worked and volunteered in mental health and social services with multicultural populations, particularly those from marginalized communities and served as a Board Member for the Broward Association for Marriage and Family Therapy in Florida. As a two-time recipient of AAMFT’s Minority Fellowship Award, her research focused on the prevalence of racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States. Her most recent publication was a chapter, “To Thine Own Self Be True” (2023) in A. G. James and L. A. Anderson’s (Eds.) Letters to a Young Practitioner: Essays of Advice (pp. 63-68). She continues to address racial and ethnic disparities and SDoH, primarily among the underserved, women of color, and children in the US and Zimbabwe through various projects and presentations.

Laurie L. Charlés, PhD, is a licensed marriage and family therapist and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. Over the past dozen years, she has delivered family systems training and supervision support in humanitarian contexts in multiple countries, including in Syria, Libya, and Lebanon; in the Central African Republic, DRC, Burundi and Cameroun, and in Guinea, West Africa during the EVD2014 outbreak response. Her most recent consultations have been as an international trainer for the United Nations Office in Vienna, working to deliver the UNODC Treatnet Family package to practitioners in Central, South, and Southeast Asia, and as a consultant to create a grassroots toolkit for practitioners engaged in Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Initiatives in Sri Lanka. She has twice been a Fulbright scholar: in 2017-2018 as a Fulbright Global Scholar Program Fellow in Kosovo and Sri Lanka, and in 2010 as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar in Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Family Therapy from Nova Southeastern University and an MA in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She is author/editor of seven books, most recently International Family Therapy: A Guide for Multilateral Systemic Practice in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (2021, Routledge).

Laurie L. Charlés, PhD, is a licensed marriage and family therapist and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. Over the past dozen years, she has delivered family systems training and supervision support in humanitarian contexts in multiple countries, including in Syria, Libya, and Lebanon; in the Central African Republic, DRC, Burundi and Cameroun, and in Guinea, West Africa during the EVD2014 outbreak response. Her most recent consultations have been as an international trainer for the United Nations Office in Vienna, working to deliver the UNODC Treatnet Family package to practitioners in Central, South, and Southeast Asia, and as a consultant to create a grassroots toolkit for practitioners engaged in Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Initiatives in Sri Lanka. She has twice been a Fulbright scholar: in 2017-2018 as a Fulbright Global Scholar Program Fellow in Kosovo and Sri Lanka, and in 2010 as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar in Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Family Therapy from Nova Southeastern University and an MA in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She is author/editor of seven books, most recently International Family Therapy: A Guide for Multilateral Systemic Practice in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (2021, Routledge).

.

REFERENCES

Ali, M. A., Zendo, S., & Somers, S. (2021) Structures and strategies for social integration: Privately sponsored and government assisted refugees, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2021.1938332

Bischoff, R. J., Springer, P. R., & Taylor, N. (2017). Global mental health in action: Reducing disparities one community at a time. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(2), p.276-290. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12202

Caron, R. M., & Adegboye, A. R. A. (2021). COVID-19: A syndemic requiring an integrated approach for marginalized populations. Frontiers in Public Health (9) 675280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.675280

Charlés, L. & Lewis, F. (2022) Family evacuation after the collapse of Afghanistan: 100,000+ stories yet to be told. Family Therapy Magazine. Alexandria, VA: AAMFT.

Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H. Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 394(10194), pp. 240-248.

Dillon, P. [@IOM Ukraine]. (2022, March 15). Ukraine war creating a child refugee almost every second: UNICEF.[Tweet; https://twitter.com/IOMUkraine/status/1503719684314701826?s=20&t=WosH3z1qHj8ovTcAMLFuqA] Twitter.

Hynie, M., McGrath, S., Bridekirk, J., Oda, A., Ives, N., Hyndman, J., Arya, N., Shakya, Y., Hanley, J. & McKenzie, K. (2019). What role does type of sponsorship play in early integration outcomes? Syrian refugees resettled in six Canadian cities. Refuge, 35(2), 36-52. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064818ar

Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation. New York: W.W. Norton.

Makombe, E. K. (2021). “Between a rock and a hard place”: The coronavirus, livelihoods, and socioeconomic upheaval in Harare’s high-density areas of Zimbabwe. Journal of Developing Societies, 37(3), p.275-301.

Schencker, L. (2019). Chicago’s lifespan gap: Streeterville residents live to 90. Englewood residents die at 60. Study finds it’s the largest divide in the U.S. Chicago Tribune. June 6, 2019. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-chicago-has-largest-life-expectancy-gap-between-neighborhoods-20190605-story.html.

Solar, O., & Irvin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on social determinants of health. Social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (Policy and Practice). World Health Organization.

Tomasi, A-M., Slewa-Younan, S., Narchal, R., & Rioseco, P. (2022). Professional mental health help-seeking amongst Afghan and Iraqi refugees in Australia: Understanding predictors five years post resettlement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031896

UNHCR. (2022). UNHCR operational data support. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

World Health Organization. (2022, March 16). Social determinants of health https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Further Resource

United Nations. (2022, March). Ukrainian war creating a child refugee almost every second: UNICEF. https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/03/1113942

Other articles

Decisions, Decisions, Decisions: Considerations Regarding License Portability and Compacts

State licensure has provided many significant advantages for MFTs and their clients, and the long and ultimately successful battle to obtain licensure in all 50 states ranks as the most significant accomplishment in the growth of the profession in the United States.

Transmitting Hypervigilance Through Intergenerational Trauma: Recommendations for Marriage and Family Therapists

African Americans have been shown to display distrust and hypervigilant behavior against people of authority and knowledge. When relaying their experiences to their peers and family members, hypervigilance seems to spread throughout the community resulting in more distrust.

Tiffany D. J. Sanders and Eman Tadros, PhD

Understanding the Effects of Social Media on the Relationship Between Parents and Adolescents

Social media, accessed through electronic devices, has been positively correlated with depression and anxiety. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), about one-fifth of Americans see digital influences of social media as a source of stress, as they have become a vital component of daily functioning (APA, 2017).

Christopher A. Chandroo, MS and Tziporah Rosenberg, PhD