Recently, an acquaintance of an acquaintance (let’s call her Dina) heard that I was a therapist and an educator and asked if she could chat with me (this write-up was approved by her). She shared that she discovered her therapist was using AI to partially conduct their sessions.

While I won’t go into how the issue came to light, Dina mentioned that she felt shock and anguish. She was terrified that her protected health information (PHI) and feelings were “out on the internet.”

The client confronted her therapist, who admitted to using poor judgment, apologized, and confessed that they were feeding prompts to AI to “ensure that their therapeutic responses to Dina were as helpful as possible.” The therapist reassured Dina that they were not recording the conversations, nor was PHI involved.

Dina shared with me that this was a new therapeutic relationship, and she felt completely misled and blindsided. She also wondered why her therapist was not competent enough to conduct therapy without consulting AI. So, she quickly decided to terminate therapy and then reached out to me to ask if this “use of AI in a therapy session was normal.”

I empathized with her feelings while acknowledging that her experience was not unique.

Fact: AI is widely used by clients, therapists, and MH organizations.

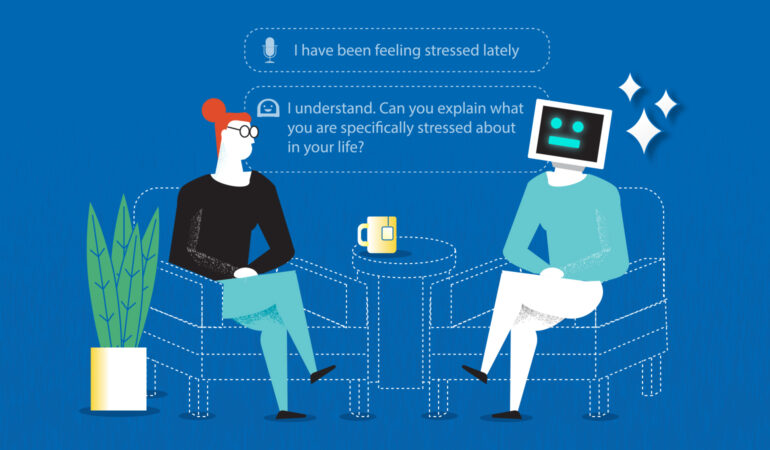

As an educator, I’ve had to reflect on how to create structure, policies, and best practices for graduate psychotherapy trainees, some of whom lean towards utilizing AI for assistance. It seems easy to create a treatment plan for a new client using AI or to enter prompts to quickly figure out how to phrase something for a client. Mental health organizations have also harnessed AI’s potential in everything from managing paperwork to enhancing training, tracking performance, conducting supervision, and analyzing trends in data.

But what are the minimum ethical standards with respect to AI use in therapy? And what are best practices with AI in training therapists?

The truth is that a lot of mental health professionals and policy makers are playing catch-up in this space. I shared with Dina what our AAMFT code of ethics states, and how some states and professional associations are adding caveats and limits on the use of AI in therapy. It’s still a work in progress. Regardless, clearly Dina’s former therapist should have been fully transparent and sought written consent prior to using AI to guide the contents of the session, if that was ok at all, based on their license and location.

Legally, the contents of psychotherapy sessions and PHI are protected (within limits). When therapists disclose client information with supervisors or for billing purposes, they obtain prior written consent for this. When supervisors use AI to help their trainees improve therapeutic interactions via the use of specialized software or generic AI programs, this too needs to be clearly explained to clients, or the information encrypted/deleted to protect PHI.

Dina and I discussed her options going forward. I sincerely hoped she would give another therapist a chance. I did advise her to ask her next therapist the question below. And going forward, I hope all clients will ask this same question of their current or future therapists:

“Please tell me all the ways in which you and/or your organization actively use AI to plan, conduct, and manage psychotherapy.”

But what are the minimum ethical standards with respect to AI use in therapy? And what are best practices with AI in training therapists?

Mudita Rastogi, PhD, LMFT, is an AAMFT professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations and is the CEO and Founder of Aspire Consulting and Therapy, PLLC, in the Chicagoland area. Her areas of expertise include systemic thinking, trauma, executive coaching, family businesses, and higher education. She is currently focused on amassing knowledge of AI. muditarastogi@gmail.com / Clinical Aspire / Consulting Exec Happiness

Other articles

Fostering Intersectional Body Image

What happens when you say the word ‘fat’? Does it roll off your tongue, or do you tense up like you’re saying a word that shouldn’t be said? Growing up, I was uncomfortable with hearing my body being described as fat since I received the message that being fat was a bad thing. This fear of getting fat was a primary focus of conversations, yet being fat was supposed to be concealed and fade into the background.

Josh Bolle, PhD

Could Pebbling be the New Practice for Relational Aliveness?

Every day, despite what life demands from us as educators, friends, daughters, and partners, both of us find ways to exchange little clips, memes, and funny stories via social media. These are meaningful digital breadcrumbs that keep us connected throughout the day as we experience life in both personal and professional roles.

Danna Abraham, PhD & Afarin Rajaei, PhD

Family-Centered Care in Psychiatric Residential and Inpatient Treatment for Youth

Family therapists generally believe in healing family relationships as a means to mitigate mental health challenges of a child. However, youth may have such extreme or chronic conditions that inpatient or residential placement is needed. For some families, having a child in these environments can be a respite; a break from managing the needs of a struggling child.

Guy Diamond, PhD, Payne Winston-Lindeboom, MA, Samantha Quigneaux, MA, Hannah Sherbersky, DClinPrac, Ilse Devacht, ClinPsy, & Michael Roeske, PsyD