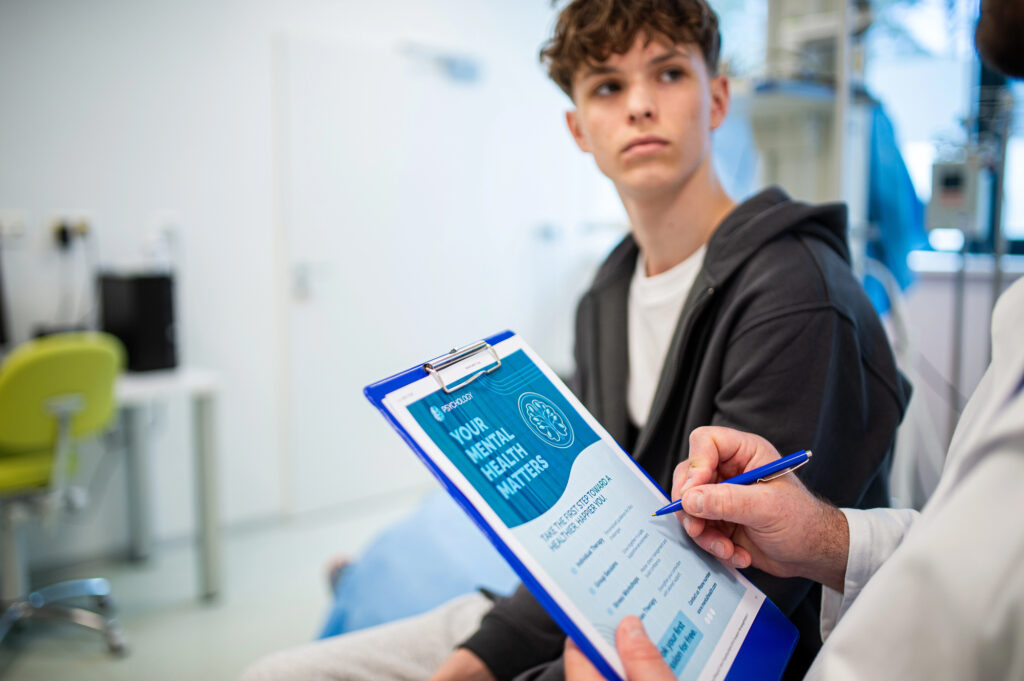

Family therapists generally believe in healing family relationships as a means to mitigate mental health challenges of a child. However, youth may have such extreme or chronic conditions that inpatient or residential placement is needed. For some families, having a child in these environments can be a respite; a break from managing the needs of a struggling child. Alternatively, some families may feel shame and guilt about sending their child out of the home and worry about their well-being (American Association of Children’s Residential Centers, 2009). In addition, youth may welcome a chance to get away from conflicts or stressors in the home, school, or community. Yet some youth may be angry or anxious about going into placement.

While residential programs tend to be “more expensive, intrusive, and restrictive than community-based alternatives” (Lyons et al., 2009, p. 72), they are useful services in the continuum of mental health services for children, adolescent and young adults. Unfortunately, when youth go to placement, parents often stop receiving services. While parents often participate in intake, treatment planning, and discharge, they less often participate directly in the therapy process (Barken & Lowndes, 2018). Individual and group therapy continue to be the dominant treatment modality in residential and inpatient care settings (Herbell & Ault, 2021). As a result, parents may not benefit themselves from the youth’s treatment process, nor are they better prepared to assist the youth in returning home and reintegrating into the community.

Given these challenges, many scholars have encouraged residential care facilities to become more family-centered (see Winston-Lindeboom et al., 2025, for a review). Groups such as the International Work Group on Therapeutic Residential Care (Whittaker et al., 2016), the American Association of Children’s Residential Centers (AACRC; 2009), and the Residential Care Consortium (Affronti et al., 2009) have outlined principles, guidelines, and practices for inclusion of families in these settings. However, many patients, staff and organizational barriers can hinder these efforts (Winston-Lindeboom et al., 2025).

To address these challenges, the authors of this report have been involved in three different efforts to help residential and inpatient programs become more family focused. The first project involved integrating Attachment-based Family therapy (ABFT; Diamond et al., 2014; 2021) into standard-of-care at a large, multi-state, psychiatric residential system. The second program, Attachment-based Care for Teams (ABC4Teams), provides an attachment informed milieu philosophy to build a clinical culture of safety and trust (Devacht et al., 2019; Devacht & Carlier, 2023). The third program, the Inpatient Child and Mental Health Services [I-CAMHS]; Sherbersky, 2023), brings a family systems organizational philosophy to inpatient treatment environments. This article briefly reviews these models to demonstrate what a family-centered program might look like in these controlled settings.

Incorporating attachment-based family therapy into Newport Healthcare

In 2018, Newport Healthcare, a large multistate youth and young adult psychiatric residential system, adopted ABFT as the family therapy model throughout the organization. ABFT is an empirically supported, semi-structured, emotion-focused, and process-oriented treatment protocol. All family therapists receive ABFT training in the first year of employment, which involves a three-day workshop followed by one year of biweekly supervision. Therapists also attend a three-day advanced training, which leads to a level two ABFT certification. Promising and motivated therapists receive additional training and become clinical supervisors and trainers. All non-family therapy clinical staff also attend a one-day ABFT workshop in order to socialize them to the goals of the family therapy.

Rather than focusing on symptom reduction, the ABFT targets common family processes (e.g., increasing warmth, decreasing conflict, improving parental teamwork, working though family traumas).

Several features of the ABFT model make it a good fit for residential or inpatient programs. First, the treatment manual provides a unique structure and focus that gives treatment direction and goals. This is helpful in a busy clinical environment where family therapy structure and goals are needed. Five treatment tasks focus therapists on particular family and therapeutic processes that cut through the myriad of complaints and concerns that families bring to residential or inpatient care. These therapy tasks, or modules, allow the therapy to move forward in a stepwise fashion. Second, the model focuses on fundamental issues of attachment. This shifts the therapy from behavior management to relational repair; thus, taking advantage of the child being in a controlled environment, where staff, not parents, manage program compliance. Parents are put on a “behavioral management holiday,” freeing them to focus on repairing family trust and communication. Finally, the model is transdiagnostic and can be implemented with the wide age range and diagnostic diversity often presenting in these environments. Rather than focusing on symptom reduction, the ABFT targets common family processes (e.g., increasing warmth, decreasing conflict, improving parental teamwork, working though family traumas). These challenges show up within many families regardless of diagnosis, age, gender, sexuality or race.

The first meeting with the family at Newport is an educational orientation to the program where staff explicitly lay out the interpersonal ABFT goals for the family therapy (relational repair). This is revisited in a more clinical approach in the first formal family therapy sessions. The family therapist then uses individual meetings with the youth alone to identify relational ruptures and prepare youth to discuss these ruptures with their parents. ABFT goals are supported by individual therapists and counselors using other treatment modalities (e.g., EMDR, CBT, DBT, group, and art therapy) to help patients articulate these relational traumas and disappointment. Simultaneously, the family therapist meets alone with the caregivers, who often come to therapy feeling hopeless and helpless. Conflicts about parental teamwork also get addressed. Therapists will also explore how parents’ own attachment history impacts their parenting. Parents then become more motivated to learn emotionally focused parenting skills.

Returning to conjoint family sessions, therapists create a corrective attachment experience: parents listen while their child talks about difficult feelings. Being away from home sometimes helps youth to speak honestly and for parents to show more patience. If youth learn how to speak up and parents show sincere interest and empathy, the belief is youth begin to feel less emotionally reactive. As anger and distrust dissipate, youth begin to turn to parents for support and comfort, establishing a new found trust and foundation for collaborating on future expectations and returning home. An ABFT informed discharge summary helps outpatient therapists build on the progress made during the admission. While it is hard to account for what creates patient change in residential or inpatient care, outcomes from Newport (Newport Healthcare, 2023) have been positive.

The ABC4Teams Program

ABC4Teams (Devacht et al., 2019; Devacht & Carlier, 2023) is a multi-phased training program that brings a trauma-informed, attachment promoting clinical framework to a treatment team. In particular, the model extends the ABFT framework to the milieu and into team collaboration relationships, creating an integrated program involving administrators, physicians, educators, nurses, therapists, line and support staff. This program has been used in residential, partial hospitalization, and inpatient facilities in Europe, the USA and Australia. ABC4Teams helps family members repair and strengthen their parent-child relationships, while staff serve as temporary secure base. The aim is for patients to experience the milieu as a safe learning environment rather than one focused on control and behavior management. Additionally, an attachment-based lens helps staff interpret patients’ negative behaviors as emerging from unmet interpersonal needs, rather than as treatment resistances or oppositional personality flaws.

Extending the attachment-informed clinical framework to the milieu has several benefits. First, it can support the work being done in family sessions and vice versa. For example, when the family sessions focus on past traumas, group and individual therapy can take up similar themes (e.g., a group session on divorce). When patients ”act out” the unit rather than focusing on extinguishing the behavior (e.g., conflicts, resistance), staff might link it to the difficult family session that morning. In this way, conflicts on the unit become therapeutic opportunities rather than barriers to treatment. Second, patients and caregivers experience the staff as more unified in their approach; all clinical and milieu staff have a shared understanding, clinical vocabulary, intervention strategy and desired outcome. Finally, staff morale and job satisfaction may increase when the disconnect between frontline staff and clinical staff can be reduced; all staff may feel valued as part of the clinical team with shared and unique contributions.

Additionally, the ABC4Teams program does not impede the use of other treatments or milieu components already in place, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or dialectic behavior therapy. Facilities can continue using their current clinical programming. The attachment lens, however, gives an overarching framework that grounds these interventions in a more developmental, strength-based, family-centered framework. The program can be implemented regardless of the age of the patients or diagnosis.

The program consists of three phases. Phase one is a pre-training needs assessment for the milieu/organization. This helps to understand the organization’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities and to prepare for implementation. In the second phase, all family therapists on the unit are trained in ABFT. Meanwhile, all staff on the unit participate in a three-day, face-to-face training course in the ABC4Teams framework. The first day, staff learn theory, and practice-based exercises on attachment, development and human learning processes. The second day focuses on emotion focused relational skills. The third day promotes the formation of a secure learning environment within the treatment facility and, in parallel, on the security and safety of team processes. This training aims to increase collaboration between patients, family members and day and clinical staff. At the end of phase two, the training phase, a “change agent” is identified and trained (usually the family therapist) who will be responsible for supervising the unit in ABC4Teams. This is essential for full integration of the model. The third phase focuses on sustainability. In includes five meetings with staff and five meetings with the change agent. Overall, training in ABC4Teams takes about 150 hours and usually occurs over the course of a year. This is a systems change approach not an individual change model.

The program consists of three phases. Phase one is a pre-training needs assessment for the milieu/organization. This helps to understand the organization’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities and to prepare for implementation. In the second phase, all family therapists on the unit are trained in ABFT. Meanwhile, all staff on the unit participate in a three-day, face-to-face training course in the ABC4Teams framework. The first day, staff learn theory, and practice-based exercises on attachment, development and human learning processes. The second day focuses on emotion focused relational skills. The third day promotes the formation of a secure learning environment within the treatment facility and, in parallel, on the security and safety of team processes. This training aims to increase collaboration between patients, family members and day and clinical staff. At the end of phase two, the training phase, a “change agent” is identified and trained (usually the family therapist) who will be responsible for supervising the unit in ABC4Teams. This is essential for full integration of the model. The third phase focuses on sustainability. In includes five meetings with staff and five meetings with the change agent. Overall, training in ABC4Teams takes about 150 hours and usually occurs over the course of a year. This is a systems change approach not an individual change model.

Inpatient Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services Program (I-CAMHS)

In 2011, National Health Services in England launched a service transformation program that aimed to improve the quality of care and outcomes for children and young adults in community mental health systems and eventually inpatient services. One program in Southern England took a family systems approach to the training (Sherberskyet al., 2023). It emphasizes evidence-based treatments and outcome monitoring, clinical supervision from a family systems framework, and engaging family members deeper into the treatment process. The program uses family systems theory to help program staff appreciate how the quality of interaction between clients, parents and staff impact and reflect the therapeutic culture of the organization. This framework helps reduce the silo of departments and promotes collaboration and interdependence of staff at all levels of the organization. The program also aims to elevate the importance of family involvement during treatment. Parents are viewed as essential partners in the process. Family therapy becomes a core element of treatment rather than an optional auxiliary service. Both ABFT and ABC4Teams have been incorporated into I-CAMH to help consolidate these ideas.

In general, the program encourages self-reflection, shared decision-making, and adoption of a more developmental and attachment informed framework on the milieu itself.

Staff from all departments (i.e., administrators, clinical staff, line, housing staff) participate to assure representation and multiple perspectives on the functioning of the program. Sometimes, these groups are brought together across several hospital systems to promote cross-hospital learning. In addition to didactic elements of the program, the format encourages reflective conversations between staff about how to move toward more within and between department collaboration and parent inclusion. A systems analysis helps the unit assess barriers to family inclusion. Staff receive training in child and family development/life cycle, systemic assessment and case formulation, and how to understand the emotional and organizational culture of a family. In general, the program encourages self-reflection, shared decision-making, and adoption of a more developmental and attachment informed framework on the milieu itself.

After training, the unit staff are believed to better understand how to work as a collaborative system (that includes the unit staff, patients, and families) and better consider issues pertaining to culture, power imbalances, and group dynamics. Specifically, the training promotes how the patient’s family can be more involved in decision making, treatment, transition and discharge. Teaching staff how to collaborate with parents is enhanced by involvement of a parent with “lived experience.” Hearing stories from the families themselves often enriches the staff learning experience. Staff are also invited to reflect on their own attachment patterns and how particular dynamics between the parent/youth/staff triad may trigger responses in themselves. Finally, sensitizing staff to the liability issues of parent involvement (i.e., consent) helps reduce staff anxiety about greater family participation in the program.

Discussion

Residential and inpatient services are an important part of the mental healthcare system (Lyons et al., 2009). These programs reviewed here emphasize family focused organizational change and the need for a unified theoretical framework to help guide the transformation. The three programs also emphasize attention to the culture of the clinical environment, recognizing that when units become more aware of own culture that unit functioning improves. All three programs elevate the role of caregivers in the clinical process, including involvement in admission, programing and discharge, and the therapy work itself. Finally, each program promotes ABFT as a central intervention in the mix of a multi-modal treatment program by focusing the treatment on core interpersonal family dynamics rather than behavioral management. This modality cuts through the myriads of family problems that often contribute to youth psychiatric distress and focuses treatment on reestablishing the family as a secure base for patients as they work through clinical challenges and prepare to return home.

Guy Diamond, PhD, is an AAMFT professional member and an Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and President of ABFT International Training Institute.

Payne Winston-Lindeboom, MA, is a Research Scientist at Newport Healthcare. In this position, Winston-Lindeboom explores data, asks important questions, assesses the quality of services, and helps to advance the field through the publication of research findings.

Samantha Quigneaux, LMFT, is an AAMFT professional member and the National Director of Family Therapy Services at Newport Healthcare.

Hannah Sherbersky is a Family and Systemic Psychotherapist, Associate Professor at the University of Exeter and CEO of the Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice UK.

Ilse Devacht, PhD, is a family therapist in a residential therapeutic unit for middle childhood children at UPC KU Leuven. She is the developer of ABCT4Teams, and an approved Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT) therapist, trainer, and supervisor.

Michael Roeske, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and currently oversees the Newport Healthcare Center for Research and Innovation. His research interests focus on adolescent and young adult patient populations and their response to treatment.

Affronti, M. L., & Levison-Johnson, J. (2009). The future of family engagement in residential care settings. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26(4), 257–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710903382571

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers (2009a). Redefining residential: Becoming family-driven. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26(4), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710903256239

Barken, R., & Lowndes, R. (2018). Supporting family involvement in long-term residential care: Promising practices for relational care. Qualitative health research, 28(1), 60-72.

Brown, J. D., Barrett, K., Ireys, H. T., Allen, K., Pires, S. A., & Blau, G. (2010). Family-driven youth-guided practices in residential treatment: Findings from a national survey of residential treatment facilities. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 27(3), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2010.500137

Devacht, I., Bosmans, G., Dewulf, S., Levy, S., & Diamond, G. S. (2019). Attachment‐based family therapy in a psychiatric inpatient unit for young adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(3), 330-343. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1383

Devacht, I., & Carlier, E. (2023). Do they cross the bridge when they come to it? Young adult’s engagement in attachment-based family therapy as part of inpatient care. Journal of Family Therapy, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12437

Diamond, G., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. (2021). Attachment-based family therapy: Theory, clinical model, outcomes, and process research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 294, 286-295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.005

Diamond, G. S., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. A. (2014). Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents. American Psychological Association.

Herbell, K. S., & Breitenstein, S. M. (2020). Parenting a child in residential treatment: Mother’s perceptions of programming needs. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 42(7), 639-648. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1836536

Lyons, J. S., Woltman, H., Martinovich, Z., & Hancock, B. (2009). An outcomes perspective of the role of residential treatment in the system of care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26(2), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710902872960

Newport Healthcare (2023). The Science of Healing 2022 Edition: Patient Outcomes and Key Findings. https://www.newporthealthcare.com/healthcare-outcomes/

Sherbersky, H., Vetere, A., & Smithson, J. (2023). ‘Treating this place like home’: An exploration of the notions of home within an adolescent inpatient unit with subsequent implications for staff training. Journal of Family Therapy, 45(4), 392-413. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12443

Whittaker, J. K., Holmes, L., del Valle, J. F., Ainsworth, F., Andreassen, T., Anglin, J., et al (2016). Therapeutic residential care for children and youth: A consensus statement of the international work group on therapeutic residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 33(2), 89-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2016.1215755

Winston-Lindeboom, P., Rivers, A. S., Roeske, M., & Diamond, G. (2025). Can Research on Family Factors in Youth Psychiatric Residential Treatment Programs Inform Efforts to Implement Family-Centered Care?. The Family Journal, 33(1), 104-114. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807241280107

Other articles

AI in the Therapy Room: A Client’s Need for Informed Consent

Recently, an acquaintance of an acquaintance (let’s call her Dina) heard that I was a therapist and an educator and asked if she could chat with me (this write-up was approved by her). She shared that she discovered her therapist was using AI to partially conduct their sessions.

Mudita Rastogi, PhD

Fostering Intersectional Body Image

What happens when you say the word ‘fat’? Does it roll off your tongue, or do you tense up like you’re saying a word that shouldn’t be said? Growing up, I was uncomfortable with hearing my body being described as fat since I received the message that being fat was a bad thing. This fear of getting fat was a primary focus of conversations, yet being fat was supposed to be concealed and fade into the background.

Josh Bolle, PhD

Could Pebbling be the New Practice for Relational Aliveness?

Every day, despite what life demands from us as educators, friends, daughters, and partners, both of us find ways to exchange little clips, memes, and funny stories via social media. These are meaningful digital breadcrumbs that keep us connected throughout the day as we experience life in both personal and professional roles.

Danna Abraham, PhD & Afarin Rajaei, PhD