Migration of People Across the Globe: An Ancient and Contemporary Circle

Every family therapist is engaged, in one way or another, with the constant and ubiquitous migration of humans across the globe. It is the nature of families, of history, and of hope, to mobilize one’s resources and one’s people, and travel in search of the future. Indeed, one of the most useful things to learn about a client family might be their lived experience of migration (or their ancestors’), past and present. Whether it is to or from the U.S., or any of the places in between, the description a family shares about their migration, like any family story, is contextual.

Families forced to leave their homes due to war and conflict are a unique category of migration story. So devastating in its potential for harm, war and conflict can make therapy clients out of any of us, precisely because of the upheaval at the point of and during the departure (Charlés, 2010).1 Families who are forcibly displaced—who leave home because certain circumstances on the ground are too dangerous for them to stay—are refugees. A refugee2 is considered to be anyone forced to leave his or her country of origin for fear of persecution.

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees the right of persons to leave their country to seek asylum in other countries. In such cases, a family flees a border en route to another, with the hopes of crossing into safety, and peace. Flights like this are international by nature. That is, they typically involve multiple state borders and many state and non-state actors. The 100,000 Afghan families evacuated to the U.S. as a result of the confluence of events in August of 2021, however, are extraordinarily unique—quite literally so. These Afghans entered the U.S. officially as “humanitarian parolees.” Humanitarian parole is a one-of-a-kind designation that “allows an individual who may be inadmissible or otherwise ineligible for admission into the United States to be in the United States for a temporary period for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.3 Truly, these 100,000 Afghan families are an international category unto themselves.

Navigating constant change: Humanitarian displacement in war and conflict-affected countries

Clinicians working with families displaced by war and conflict quickly learn that there are many different languages to navigate. In addition to the cultural shocks and linguistic barriers, the legal terminology surrounding displacement can bring heightened complexity to any therapeutic encounter. The legal terminology can also be extremely stressful for the family. It can denote a legal status, or a designation, which may then dictate how they can move through their days, and plan for the future. Understanding the terminology, both its constraints and its liberties, is a key part of the sytemic clinician’s case conceptualization, rapport building and treatment planning, and may include various stakeholders in the family’s life. Family therapists are experts in the use of systemic skills and knowledge to provide support between smaller systems, like families, and larger ones, like institutions, to encourage effective communication and collaboration between them for the benefit of the therapy process. Using these skills to navigate constant change with dignity and legitimacy is critical for families who are displaced by war and conflict.

Humanitarian emergencies command us to operate at multiple levels of attention and care

One way to conceptualize your understanding of a client family’s experience during a humanitarian disaster is to situate their circumstances in their historical and political contexts. This is parallel to what a systemic family therapist might do in a first session with any client family—we try to understand the interactional process and relationships in their systemic entirety, with an eye on the contemporary moment. It is not possible to look at context of a family system without also looking at the relational process of outside actors and institutions who have shaped and continue to shape a family’s experience of distress. To conduct therapy systemically is to engage in an endeavor with political and historical implications, for the family as well as the larger actors involved in their lives. This is even more prescient with a family who enters your therapeutic space because of war and conflict. Many questions are the same: What issue brings them in at this particular moment? What are the circumstances around the presenting issue? Who is present and who is absent and how does the condition of those relationships make sense to the family? What does the family want from you? How will they know you can be helpful to them? Who else is a part of the system, though perhaps not part of the family?

In addition to casualties—wars and violence destroy infrastructure and the institutions that sustain a society, such as the rule of law, health care, and the educational system. Violence also leads to long term physical, social, and psychological effects among survivors who have lost family members, those who no longer have the means to sustain their livelihoods, or who have experienced amputation, disfigurement, displacement, torture, abduction, sexual violence and disease (Pham, Vincka, & Weinstein, 2010, p. 98).

In addition to casualties—wars and violence destroy infrastructure and the institutions that sustain a society, such as the rule of law, health care, and the educational system. Violence also leads to long term physical, social, and psychological effects among survivors who have lost family members, those who no longer have the means to sustain their livelihoods, or who have experienced amputation, disfigurement, displacement, torture, abduction, sexual violence and disease (Pham, Vincka, & Weinstein, 2010, p. 98).

There are always larger actors involved in the system of a family’s engagement in therapy; in the case of the Afghan humanitarian evacuees, those actors are often public ones, making policy choices live on the world stage. Further, the humanitarian context may not be in the past; it may be ongoing, and happening in real time. Perhaps there are absent loved ones, missing family members, who remain at risk and in ongoing danger. Emergencies like pandemics and humanitarian evacuations have a great deal in common. Issues such as good governance, shared and equal access to public goods (like healthcare or education), and safe and secure participation in civil society become critical, every day concerns, rather than theoretical, abstract concepts. As in a pandemic, families must learn to live with constant uncertainty, disorientation or confusion about what is happening, and numerous unexpected short and long-term stressors. Overwhelming in their intensity, and often deeply unsettling in unknowable ways, humanitarian emergencies command us to operate at multiple levels of attention and care. One must appreciate the “deep grief,” as Xan Weber put it in the interview (see p. 34), which may have no end in sight. There is so much that may be unsaid. There is so much that may not be doable. Nevertheless, one’s appreciation of the humanitarian context must not get in the way of the capacity to see each family in its systemic, resourceful entirety.

A selective focus on PTSD or depression after a disaster is inappropriate because it overlooks many other MHPSS (mental health and psychosocial support) problems …. as well as ignoring people’s resources. A common error … is to ignore these resources and to focus solely on deficits – the weaknesses, suffering and pathology – of the affected group. (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2007)

Systemic family clinicians are experts at this sort of strengths-based approach, defined early on in our field by simple, elegant, and critical ideas, such as utilization (Erickson, 1980), to name but one. It is so important to heighten this sensitivity with Afghan evacuees. The international nature of the events that unfolded in the country, and the historical significance families (and family therapists) attribute to events surrounding the humanitarian evacuation are laden with meaning. Key tasks for clinicians working inside these circumstances are to identify, mobilize and strengthen the skills and capacities of individuals, families, communities and society to “bounce forward,” as Froma Walsh (2002) called it, from these events.

Families displaced by war and conflict: What we know and what we need to know

Families and individuals in families are certainly not the labels we ascribe to them; the name is not to be confused as the thing named (Bateson, 1979). Labels may help us know something about how to classify what we are seeing; however, it is helpful to be mindful that the family’s relationship to these labels or categories is most paramount. Labels to do with legal identity, residency, evacuation, and citizenship, bring to an apogee the intersectional complexity of everyday life for families who are forcibly displaced. The good news is that working inside such complexity is the métier of systemic clinicians. More good news is that we can draw on best practices from many previous humanitarian emergencies, in any effort to best support families displaced by war and conflict (IASC, 2010; Charlés & Samarasinghe, 2019; Charlés & Samarasinghe, 2016; Saul, 2013).

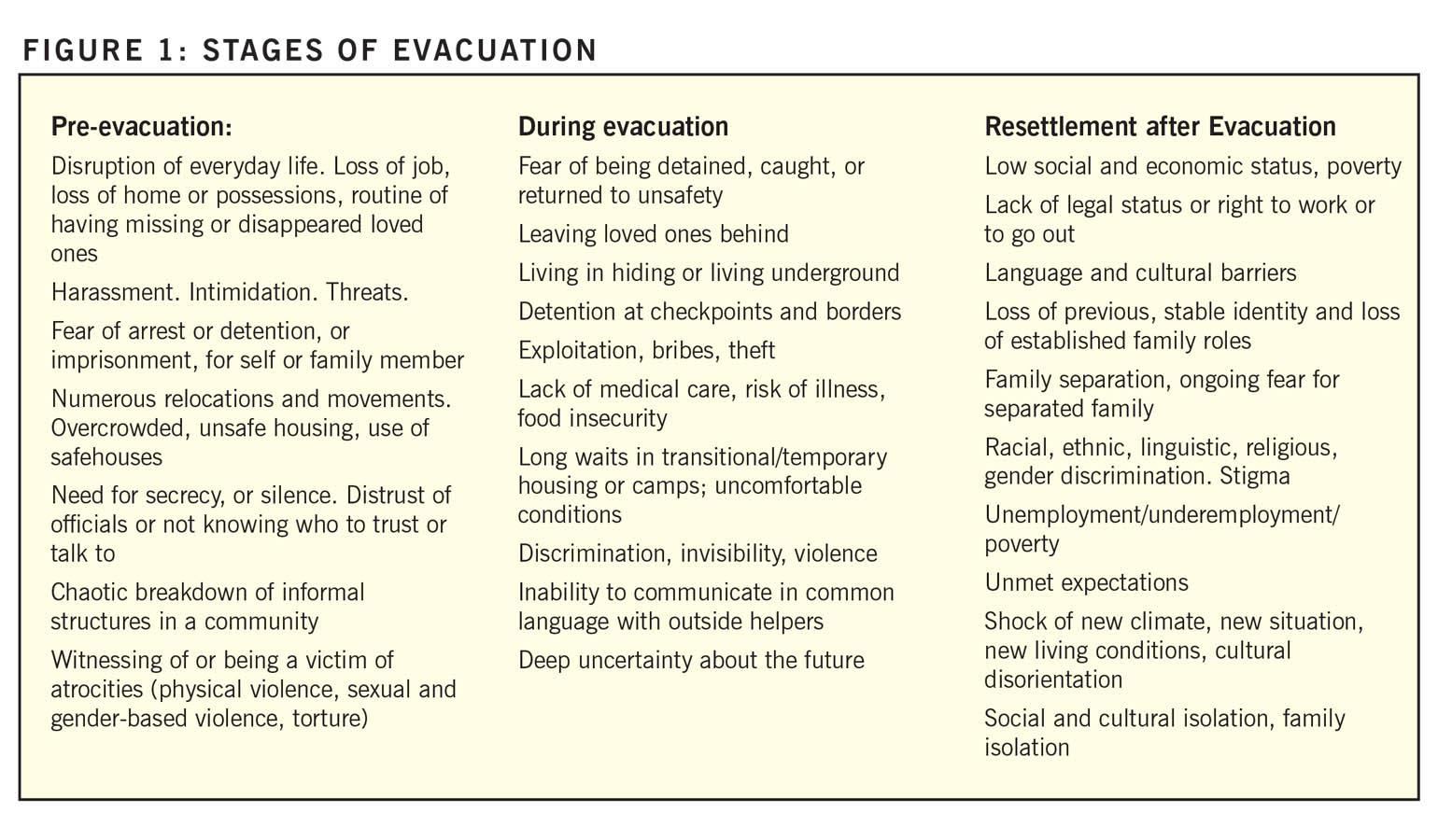

If a forcibly displaced person, such as a refugee, had a typical timeline for their flight to safety, the following events may be considered “typical.” Naming such conditions in such a way, we do not mean to imply a chronology is required for the events. Indeed, a combination of and returning to them is likely to be unique to each family. For the Afghan evacuee families, perhaps the entire list may have been relevant in a matter of hours and days, rather than weeks and months. See Figure 1 on the stages of evacuation.

In response to such complexity, the following practices can be useful in working with families who are resettled after a humanitarian emergency.

- Provide concrete assistance as appropriate, and establish yourself as a resource. Don’t just ask questions but offer suggestions, and resources.

- Talk about mental health and psychosocial support within the client’s frame of reference.

- Assist survivors through the grieving and mourning of multiple losses (i.e., Walsh, 2002; Boss, 1999).

- Assist survivors with their overall adjustment to a new environment.

- Talk with them about the future and the re-establishment of occupational and educational plans, familial roles, and responsibilities.

- Enhance working knowledge of the life experiences and resettlement issues (whether IDPs, evacuees, refugees, asylum seekers or asylees) before, during, and after their flight to safety.

- Increase your learning about the history of a people; take advantage of written histories, oral histories, country reports from governmental or NGO or human rights organizations.

- Read accounts from cultural anthropology and sociology, the arts (drama, poetry, memoirs, visual arts), and websites maintained by political or human rights organizations within the country, as well as outside.

-

Help families anticipate and plan for how to cope with potential high-stress experiences, such as a status hearing, distressing news (or lack of news) about family members still in country.

-

Assist families with unexpected experiences of violence, including criminal activity, physical harm, stigma, discrimination and racism that may occur.

At an AAMFT conference in Memphis over a dozen years ago, Charlés, Bacigalupe and Beaver (2008) outlined a list of strategies, in the form of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, relevant for supervision work and peer support for systemic clinicians working with refugees and torture survivors. Systemic skills and mindfulness have a long shelf life. We believe that the following notes, with only slight modification, continue to have some relevance for practioners doing clinical or advocacy work with Afghan evacuees. We recommend pairing these building blocks and applying them within the context of work with displaced families.

At an AAMFT conference in Memphis over a dozen years ago, Charlés, Bacigalupe and Beaver (2008) outlined a list of strategies, in the form of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, relevant for supervision work and peer support for systemic clinicians working with refugees and torture survivors. Systemic skills and mindfulness have a long shelf life. We believe that the following notes, with only slight modification, continue to have some relevance for practioners doing clinical or advocacy work with Afghan evacuees. We recommend pairing these building blocks and applying them within the context of work with displaced families.

Listening to a family’s lived experience, as they navigate the extreme nature of such unthinkable horror, is a challenge systemic clinicians have the capacity to master, given the nature of systemic theoretical concepts, and the in-depth training required to practice it.

Attitudes – Appreciation of multiple cultural perspectives; awareness of/safeguards against ethnocentricity; openness; collaborative curiosity; seeing all psychosocial support as cultural; utilizing inter-disciplinary approach to learning/teaching/supervision; self-reflection.

Knowledge – Re-evaluate therapeutic frameworks; re-evaluate cultural practices/acquire new and useful information about cultural practices; analysis of intersection of identities, contexts, privileges, and oppressions; use culturally specific interventions; develop creativity for “non-western” methods; acquire learnings from field experiences and immersion.

Skills – Breadth, and flexibility in clinical skills; ability at shifting frameworks/cultural inclusiveness, sensitivity, awareness, competency; reflexive as self of the therapist; use of community art/action/engagement; narrative and story-telling as well-being; analysis of circumstances of conflict, displacement; self-reflection.

Relational intelligence: A global, ethical imperative for the future

Relational intelligence is the forté of every systemic clinician. However, systemic clinicians are not perhaps accustomed to thinking in terms of peoples’ relational process with regard to a state (country). However, the distress that culminated in a humanitarian evacuation in Afghanistan in August, 2021, has threads in the state behavior and policy choices of many countries, certainly including the U.S., and over a long period of time. But where does one punctuate “relevance” on a timeline like this? In a place where so many international interventions have taken place? A first step is to learn something about the events, and their historical significance, as robustly as you can. Then, hold on lightly to that which you have learned (Charlés & Bava, 2021). Next, prepare to start the process all over again, but along with the family, and from the family’s point of view. Seek out supportive supervision when you find these stories challenging to hear.

Humanitarian emergencies are always part of multiple state and non-state actors’ actions and interactions. Often the emergency is the result of state behavior. Afghan evacuee families left in extremely distressing circumstances; their family members may remain in peril, in what continues to be the latest chapter in a dynamic and ongoing set of international events. Listening to a family’s lived experience, as they navigate the extreme nature of such unthinkable horror, is a challenge systemic clinicians have the capacity to master, given the nature of systemic theoretical concepts, and the in-depth training required to practice it.

Lewis (2019) conducted an explanatory, sequential, mixed-methods design study that included interviews of primary healthcare providers who worked with a youth refugee population, to learn more about the behavioral health needs that they saw in their work. According to her respondents, behavioral health support is needed with this population. Displaced youth tend to be situated between multiple systems; family therapists have the training and the mindset to include the influence of other systems in any assessment and treatment modalities. For clinicians providing integrated behavioral healthcare in Lewis’ (2019) study, participants suggested there be more on-site behavioral health providers to administer child development and behavioral health screenings. When the participants were asked to provide suggestions on how to better support displaced youth in primary healthcare, many expressed the need for more behavioral health support.

The work that family systems clinicians do requires that the family’s worldview, their beliefs, and their sense of meaning about who they are and what is happening to them are central to the interaction. Systemic clinicians would do well to scale up their already sophisticated ability and affinity to hear this content with some robust knowledge, and an international lens, while keeping an ear on the family process. This combination can bring an informed understanding that is critical to one’s ability and capacity to work effectively with families displaced by war. It is an essential for any culturally sound, evidence-informed, and socially just practice in a humanitarian context (Charlés & Samarasinghe, 2016).

AUTHOR INTERVIEW

Afghan Family Evacuees: “Not just here for themselves.”

The catastrophic displacement of Afghan evacuee families in 2021, its steps and misteps, its “before, during, and after,” whether punctuated at the point of 9/11 or some date in the years before or since, directly informs and can speak profoundly about how the family (and the family therapist) is processing the Afghan evacuees’ arrival in the U.S. How can you be helpful beyond what you already know about how to work with communities and families who have experienced this kind of distress? How to apply what you know to the context of such a catastrophe? What more do you need to learn? We recommend fearless listening, with an open heart and a systemic brain, to learn the essential details of what is the meaningful context for that family. Systemic family therapy engagement with an Afghan family, in a way that fits their worldview and which honors their hopes for the future in spite of their overwhelm about the past, is, as always, key practice. We have found supportive supervision, peer support, and work in collaborative teams, useful to manage all of the uniqueness of this work.

Systemic family therapists have the capacity to work effectively and innovatively within the type of complexity that is deeply intertwined with global forced migration. The number of displaced persons across the globe is only predicted to increase in the future. We expect the nature of future humanitarian disasters to further challenge the well-being of families, in many parts of the globe. The field as a whole is working to equip clinicians with the cultural, intersectional knowledge to help families manage multiple identities and transitions; however, we can never take what we think we know for granted. We would do well to enrich and exchange what we know, by engaging with the scholarship that focuses on the lives of families living in fragile, conflict-affected states (Charlés, 2015). A systemic clinician with such a background is a valuable asset to the many sets of professionals, systems, and healthcare teams supporting these families.

This article is offered free by AAMFT. If you are interested in accessing members-only content, join today!

1

Internal conflicts are the most prevalent type of conflict resulting in forced displacement. But family displacement can happen anywhere, in many types of circumstances. When it happens inside a country’s borders (such as when families affected by Hurricane Katrina in Louisiana migrated to Texas for safety), families may be identified as internally displaced. The International Organization for Migration defines IDPs as: “…among the most vulnerable people in the world today. Forced to leave their homes as a result of armed conflict, gross violations of human rights and other traumatic events, once displaced they nearly always continue to suffer from conditions of insecurity, severe deprivation and discrimination.”

2

Article 1(A) 2 of the 1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees defines a refugee as an individual who “owing to well founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it. In the case of a person who has more than one nationality, the term “the country of his nationality” shall mean each of the countries of which he is a national, and a person shall not be deemed to be lacking the protection of the country of his nationality if, without any valid reason based on well-founded fear, he has not availed himself of the protection of one of the countries of which he is a national.”

Laurie L. Charlés, PhD, LMFT, is a licensed marriage and family therapist and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. Over the past dozen years, she has delivered family systems training and supervision support in humanitarian contexts in many countries, including Syria, Libya, and Lebanon; in the Central African Republic, DRC, Burundi and Cameroun, and in Guinea, West Africa during the EVD2014 outbreak response. Her most recent projects have been as an international trainer for the United Nations Office in Vienna, working to deliver the UNODC Treatnet Family package to practitioners in Central, South, and Southeast Asia, and as a consultant to create a grassroots toolkit for practitioners engaged in Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Initiatives in Sri Lanka. She has twice been a Fulbright scholar: in 2017-2018 as a Fulbright Global Scholar Program Fellow in Kosovo and Sri Lanka, and in 2010 as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar in Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Family Therapy from Nova Southeastern University and an MA in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She is author/editor of seven books, most recently International Family Therapy: A Guide for Multilateral Systemic Practice in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (2021, Routledge).

Laurie L. Charlés, PhD, LMFT, is a licensed marriage and family therapist and an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. Over the past dozen years, she has delivered family systems training and supervision support in humanitarian contexts in many countries, including Syria, Libya, and Lebanon; in the Central African Republic, DRC, Burundi and Cameroun, and in Guinea, West Africa during the EVD2014 outbreak response. Her most recent projects have been as an international trainer for the United Nations Office in Vienna, working to deliver the UNODC Treatnet Family package to practitioners in Central, South, and Southeast Asia, and as a consultant to create a grassroots toolkit for practitioners engaged in Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Initiatives in Sri Lanka. She has twice been a Fulbright scholar: in 2017-2018 as a Fulbright Global Scholar Program Fellow in Kosovo and Sri Lanka, and in 2010 as a U.S. Fulbright Scholar in Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Family Therapy from Nova Southeastern University and an MA in International Relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. She is author/editor of seven books, most recently International Family Therapy: A Guide for Multilateral Systemic Practice in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (2021, Routledge).

Florence Lewis, PhD, LMFT, completed her doctorate in Medical Family Therapy from East Carolina University in 2019, her Master’s degree in Marriage and Family Therapy from Purdue University Northwest in 2015, and her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Oakwood University (a historically Black University) in 2012. For her doctoral dissertation, she explored the behavioral health needs of displaced families in primary healthcare settings. As a two-time recipient of the SAMSHA Minority Fellowship, Lewis’ professional projects include unpacking African American cultural values to improve health outcomes, supporting immigrant families through the U.S naturalization process, training recommendations for international family therapists, and exploring the mental health outcomes of foreign-born U.S. military service members. Currently, Lewis lives in Northern Italy and works on a military installation supporting the special needs population.

Florence Lewis, PhD, LMFT, completed her doctorate in Medical Family Therapy from East Carolina University in 2019, her Master’s degree in Marriage and Family Therapy from Purdue University Northwest in 2015, and her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Oakwood University (a historically Black University) in 2012. For her doctoral dissertation, she explored the behavioral health needs of displaced families in primary healthcare settings. As a two-time recipient of the SAMSHA Minority Fellowship, Lewis’ professional projects include unpacking African American cultural values to improve health outcomes, supporting immigrant families through the U.S naturalization process, training recommendations for international family therapists, and exploring the mental health outcomes of foreign-born U.S. military service members. Currently, Lewis lives in Northern Italy and works on a military installation supporting the special needs population.

REFERENCES

Bateson, G. (1979) Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Dutton: NY.

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous loss. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Charlés, L. L. (2015). Scaling up family therapy in fragile, conflict-affected states. Family Process, 54(3), 545-558.

Charlés, L. L. (2010). Family therapists as front line mental health providers: Using reflecting teams, scaling questions, and family members in a primary and secondary care hospital in a war-affected region of Central Africa. Journal of Family Therapy, 32, 27-42.

Charlés, L., Bacigalupe, G. & Beaver, A. (2008, October). Refugee families: Ethical, clinical, and training practices. American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy National Conference, Memphis, Tennessee.

Charlés, L., & Bava, S. (2021). Systemic family therapy and global mental health: Reflections on professional development and training. In M. Rastogi & R. Singhe (Eds.) (K. Wampler Series Editor), Handbook of systemic family therapy (Vol. IV). New York, NY: Wiley.

Charlés, L., & Samarasinghe, G. (2016). Family therapy in global humanitarian contexts: Voices and issues from the field. New York, NY: Springer.

Charlés, L. & Samarasinghe, G. (2019). Family Systems and global humanitarian mental health: Approaches in the field. New York, NY: Springer.

Erickson, M. (1980). The nature of hypnosis and suggestion: The collected papers of Milton H Erickson on hypnosis (Vol. 1, E. L. Rossi, Ed.). New York: Irvington.

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Global Protection Cluster Working Group and IASC Reference Group for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. (2007). Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Humanitarian Emergencies. Geneva: Author.

Lewis, F. (July 2019). Identifying the unmet behavioral health needs that resettled refugee youth present within primary health care settings (Doctoral Dissertation, East Carolina University). Retrieved from the Scholarship. (http://hdl.handle.net/10342/7416)

Pham, P. N., Vincka, P., & Weinstein, H. M. (2010). Human rights, transitional justice, public health and social reconstruction. Social Science & Medicine, 70(1), 98-105.

Saul, J. (2013). Collective trauma, collective healing: Promoting community resilience in the aftermath of disaster. New York: Routledge.

Walsh, F. (2002). Bouncing forward: Resilience in the aftermath of September 11. Family Process, 41, 34-36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.40102000034.x

RESOURCES

“The Collapse of Afghanistan,” by Jennifer Brick Murtazashvili

“W5: A Family’s Journey out of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan”

IINE Virtual Town Hall on Afghan Resettlement – January, 2022

Other articles

Systemic Racism and the Asian American Community

An Interview with Johnny Kim, PhD, and Jessica ChenFeng, PhD, regarding experiences of discrimination in the Asian American and Pacific Islander community and impacts on emotional and mental health.

Goodbye to FTM in Print

Since 2002, Family Therapy Magazine has been hitting mailboxes six times a year, all over the globe, delivering clinical content, Association updates, and other news related to behavioral health happenings.

MFTs and the Lingering Problem of Child Separation at the Border

In this interview, immigration experts discuss the conditions in many of the home countries of immigrants, their arduous travel, and the challenges faced at the border which have created complex layers of emotional issues, particularly for those children separated from their parents.