Large population communicable diseases (pandemics) in general have multiple consequences, ranging from disruption of the community infrastructure, to tragic loss of life. Physically, individuals may experience an increase in medical complaints, specifically related to infectious diseases; as well as exacerbations of chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes and respiratory problems (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema).

The natural progression of a communicable disease, from its physiologically infectious state, cannot capture the complexity of individual human behavioral responses. One of the major causes of psychological distress is stress itself (the problem is the problem); watchful waiting becomes emotionally exhausting with the inundation of mass and hyper-communications, as well as the magnitude and duration of the disruptions in the basic functionalities of day-to-day life (work, home, school, childcare and access to available consumer goods and services).

Family employment instability and economic hardship can negatively affect the physical and mental well-being of children, particularly young children (Golberstein, Gonzales, & Meara, 2019; Kalil, 2013). These types of incompatible events were predominantly significant for the 77 million U.S. children ages 18 and under, nearly 24 million of whom are younger than 6 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021). Since April 23, 2020, the Household Pulse Survey has collected weekly data from U.S. adults regarding the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on themselves and their households (Urban Institute, 2020). Fear of contracting COVID-19; concerns around material hardship, job security and financial stability; and the toll of social isolation and limited social interactions places adults at risk of experiencing more frequent feelings of depression or anxiety.

Families in lower socioeconomic conditions confronted both material hardship and psychological distress prior to the pandemic (Sandstrom, Adams, & Pyati, 2019), likely exacerbating these problems of the parents’ and children’s mental health. All forms of stressors are often transmitted to children, and children’s prolonged exposure to stress is associated with poor developmental outcomes (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014).

With children being confined at home during the pandemic and coinciding with parental distress and anxiety, there may have been an environment that cultivated the potential for maltreatment.

Even though there have been some interventions for situational behavioral health issues (hot lines, telehealth, professional networking) this represents only one small portion of the population that accessed services. These individuals represent the “known” population. They have specifically been identified as having behavioral health issues. Researchers reported during the pandemic nearly a third of adults described clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety and depression (Lee, Ward, Chang, & Downing, 2020). The Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary statistics pre-pandemic, reported that parents with the lowest socioeconomic status are seven times more likely to neglect and three times more likely to physically abuse children (Sedlak, Mettenburg, Brown, Basena, & Madden, 2010). With children being confined at home during the pandemic and coinciding with parental distress and anxiety, there may have been an environment that cultivated the potential for maltreatment. Because official records may significantly underestimate maltreatment, what remains are only the “known” cases.

A second population is the “unknown.” This group represents individuals in the community who may not present to healthcare providers (either in the short term or unfortunately at some time when their wellbeing was deteriorating). For example, the hypertensive person who experiences an increase in headaches and general sickness but does not explore some of the co-occurring stressors and the behavioral changes taking place in the person’s life that eventually lead to a stroke. Many underlying behavioral health issues will not be assessed, potentially resulting in increases in sporadic healthcare costs, and over time, a diminished quality of life. Provisional data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC, 2020a; 2020b) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) indicate that approximately 81,230 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States in the 12-months ending in May 2020. This represents a concerning acceleration of the increase in drug overdose deaths, with the largest increase recorded from March 2020 to May 2020, coinciding with the implementation of widespread mitigation measures for the COVID-19 pandemic.

When there are large scale community and environment changes, such as increased isolation, multiple behavioral health stressors and overabundance of drug supply, it is “unknown” how many individuals are now needing substance use and possible abuse services.

The third category of the at-risk population is the “unknowable.” What will be the actual lifetime impact of large population communicable disease events on behavioral health? It is immeasurable. Appreciating the concept of a population fatigue syndrome lays the groundwork for a different perspective on lifespan development with implications on the physiological, psychological, and socialeconomic contextual processes of vulnerability. The concept of vulnerability expresses the multidimensionality of disasters by focusing attention on the totality of relationships in a given social situation which constitutes a condition that, in combination with environmental forces, produces a disaster (Bankoff, Frerks, & Hilhorst, 2004).

COVID-19 is a lifetime adverse event, and in effect an individually, universal traumatic event. “Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual wellbeing” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). The pandemic has set in-motion a cascade of future consequences, which are heterogenous. Even though the pandemic was “collective,” there will be no one unitary life-time experience. As in the Adverse Childhood Events studies that reported a linear rise between childhood events and lifetime physical and behavioral health outcomes, pandemic sequalae may be experienced as pandemic fatigue.

Taking in consideration all world-wide events, the population is developed differing perspectives of the personal/societal impact of communicable diseases in general. Many voiced that sheltering in-place and social distancing is the better universal approach to protection—others voiced fervent opinions in resentment that became more intensified as the number of cases and deaths changed and local authorities and pundits required the population to comply to restrictive directives.

During this primary phase, some of the biopsychosocial feelings that individuals may re-experience include: fatigue, trouble initiating or maintaining sleep, chest pain, shortness of breath, tightness in the throat, palpations and anxiousness, isolation and despair.

Secondary fatigue spans the time that a seasonal event, epidemic, or pandemic is officially designated. This becomes a time of sensory overload. The basic human response of flight-flight-freeze are heightened. During this time, individuals are faced with the reality that life is always in flux. Thoughts and emotions become overpowering and people find themselves functioning on “auto-pilot,” and at worse, on pure exhaustion. For many, this is difficult because of the fear of separation, loss of self-agency and for those who have not recovered from the last event (viral infection and infection like symptoms), it becomes very disheartening. If the crisis goes on for any extended length of time, family relationships are stressed, economic resources are strained, and the impact becomes even more profound for the socially vulnerable and especially for the marginalized populations. Once again, daily routines and relationships are disrupted, burdened, and compounded.

During the secondary phase, some of the biopsychosocial feelings individuals may have are more intense experiences of: anger, irritability, panic, meaninglessness, and apathy.

Tertiary fatigue is a longer lasting and pragmatic process. The central issue during this phase is that of control. An individual’s ability to have a sense of influence in their life circumstance is diminished. Following a large population communicable disease event, there will be numerous forces at work. Previous community-based resources and providers may be limited or no longer in existence. It is not easy to capture and define a specific term that actually captures the span of variable human experiences in a post COVID-19 world. However, the biopsychological functionality of a population may be conceived not just in terms of hard and fast categorical terms (depression, anxiety, etc.) but may be more reflected as a continuum where the individual’s life is calculable along a continuum of livable and doable or lessening so.

The fundamental problem is what has been addressed earlier pertaining to the “known, the unknown and the unknowable”. The known population of those diagnosed with behavioral health conditions are being able to measure things like medications, clinic visits, and hospitalizations that are relatively easy to count; however they reveal only a small portion of the total at-risk and in-need population in our society.

What is the actual number of individuals who would benefit from behavioral health services? What is the true magnitude of the unknown and unknowable population? What is appreciable, is that people exposed to uncontrollable events experience psychosocial distress. Any event that disrupts normalcy of a community impacts an individual’s biopsychosocial resources and assets. Communicable disease will obviously continue; times of great emotional upheaval will be re-experienced, and the continuum of vulnerability will remain.

The behavioral health professional community is on the brink of large-scale disruption. And while communicable diseases, natural and man-made disasters, or catastrophic events will never be completely eliminated, the ability to identify large population behavioral health issues earlier, intervene proactively, and better understand the magnitude of progression in communities will allow us to address trends, and challenges during pandemics. COVID-19 has shaped the way we deliver care forevermore. The future will need to be focused not only on the individual, but on the unknown and unknowable population.

What is appreciable, is that people exposed to uncontrollable events experience psychosocial distress.

Gary L. Kesling, PhD, LPC, LMFT, NCC, CCTP, D.A.A.E.T.S., F.A.A.E.T.S., is an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow designation. He is a marriage and family therapist who practices in North Richland Hills, TX. He is a Population Behavioral Health Consultant-Liaison, Diplomate and Fellow – Healthcare Administration (Healthcare Administration Credentialing Commission), Fellow and Diplomate – American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, and Certified Mental Health Integrative Medicine Provider (CMHIMP).

Gary L. Kesling, PhD, LPC, LMFT, NCC, CCTP, D.A.A.E.T.S., F.A.A.E.T.S., is an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow designation. He is a marriage and family therapist who practices in North Richland Hills, TX. He is a Population Behavioral Health Consultant-Liaison, Diplomate and Fellow – Healthcare Administration (Healthcare Administration Credentialing Commission), Fellow and Diplomate – American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, and Certified Mental Health Integrative Medicine Provider (CMHIMP).

REFERENCES

Bankoff, G., Frerks, G., & Hilhorst, D. (2004). Mapping vulnerability: Disasters, development and people. London: Earthscan.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a, December 14). CDC health alert network advisory: Increase in fatal drug overdoses across the United States driven by synthetic opioids before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. CDCHAN-00438. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b, December 17). Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. Atlanta, GA: Author.

Golberstein, E., Gonzales, G., & Meara, E. (2019). How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Economics, 28(8), 955-70.

Kalil, A. (2013). Effects of the great recession on child development. Annals of the American Academy 650(1).

Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., Chang, O. D., & Downing, K. M. (2021). Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105585

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2014). Excessive stress disrupts the architecture of the brain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Sandstrom, H., Adams, G., & Pyati, A. (2019). Wellness check: Material hardship and psychological distress among families with infants and toddlers. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Sedlak, A., Mettenburg, J., Brown, J., Basena, M., & Madden, K. (2012). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4) [Dataset]. National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. https://doi.org/10.34681/Z40W-2C07

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Author.

Urban Institute. (2020). Stabilizing supports for children and Families during the pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/stabilizing-supports-children-and-families-during-pandemic

U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Annual estimates of the resident population by single year of age and sex for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019 (NC-EST2019-AGESEX-RES). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

Other articles

Advancing the profession and practice of marriage and family therapy

In 2021 the AAMFT Board of Directors approved an updated Strategic Plan. The introduction of the Plan states: AAMFT is a responsive and nimble association, attuned to the contexts of our evolving environments and adaptive to circumstances that impact the profession and practice of systemic and relational therapies.

Oh, The Places We’ll Go —AAMFT Events in 2022 and Beyond

When we have talked about AAMFT events in the past, key considerations have been how we can meet members’ needs, advance our profession, and continue to build community within our association.

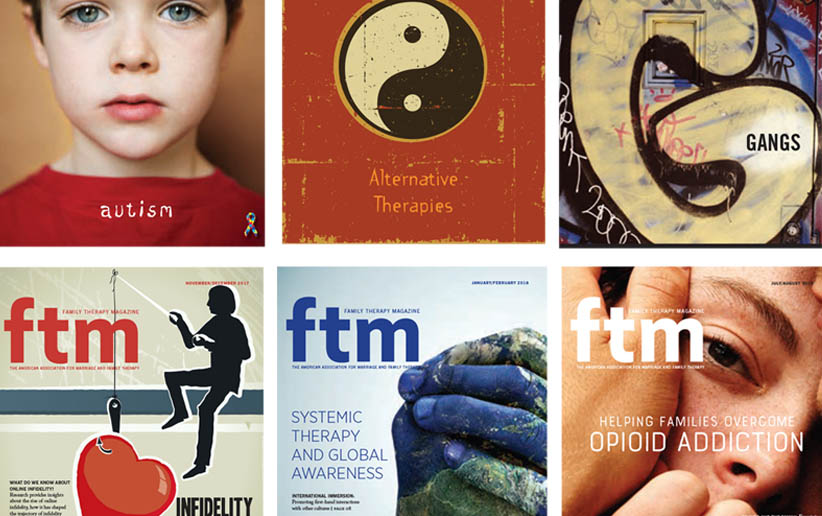

Goodbye to FTM in Print

Since 2002, Family Therapy Magazine has been hitting mailboxes six times a year, all over the globe, delivering clinical content, Association updates, and other news related to behavioral health happenings.