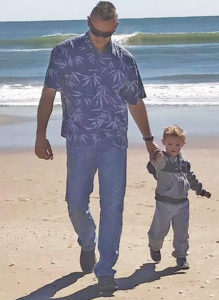

My wife and I catapulted into the special needs world with the birth of our son, Kaydan, who was born with Down syndrome. As a clinician and an Army chaplain, I thought I was well equipped for what lay ahead, but was mortified when I learned that many of the marriages with special needs children dissolve. I quickly realized that my own marriage was at risk and I did not even understand why. While the average divorce rate in the U.S. has held near 50%, limited data suggest that marriages with a special needs child face a divorce rate as high as 70-80% (Freedman, Luther, Zablotsky, & Stuart, 2011).

The special needs marriage defined

My working definition of what I term the special needs marriage is one in which one or more children are born with, adopted, or later receive a diagnosis, be it physical, developmental, or behavioral, that effects the normal or typical flow of marital life and connection. The degree to which a marriage is impacted can vary greatly. For example, a child diagnosed with autism who is still high functioning may not demand the same energy and support as the child born with cerebral palsy bound in a wheel chair. One could also surmise that there is a spectrum or continuum for the special needs marriage. The common denominator and hypothesis I would add, is that the presence of a special needs diagnosis does affect the marriage. Parenting is challenging enough, add the dimension of having a special needs child and the impact can subtlety but distinctly evolve and develop over time. With that, we will explore some specific areas that define and shape the special needs marriage.

The long view: Golden years

Perhaps the most overlooked aspect of having a special needs child is the long-term impact. Will this child be able to launch into life? Go to college? Get married? Live independently and maintain a job? The real underlying question for couples is: Will this child live with us for the rest of our lives? In the hours after our son’s birth, my mind ran wild with the endless scenarios and possibilities that could someday be reality. The questions, some of which go unspoken, are daunting: What will the golden years of retirement look like? What will our marriage look like? Will it survive until then and after? These questions and uncertain outcomes point to an undetermined future.

A few years ago, my wife and I attended her 25-year class reunion. We sat across from a couple who had just taken their last child to college. The couple lamented not knowing what to do with themselves now that it was just the two of them. And the fact that their child was attending college barely two hours away seemed to do little to resolve their emotional discontent as new “empty-nesters.” My frustration grew as others validated the seeming pity-party. I was unable to validate what on one hand was a valid experience for these parents whose child had just launched from the nest of home. On the other hand, I felt paralyzed to give language to the likely reality that my wife and I would never know what an empty-nest would look like. Many cannot grasp the emotional impact of this reality and even worse, some find it somehow humorous that our child would live with us the rest of his or our lives.

The clinical implications of this long-term element are multi-faceted. Whether working with a couple or a married individual, being aware of this dynamic alone can open doors of therapeutic relationship and provide access to deep underlying emotion. For example, simply acknowledging the uncertain future for a couple with a special needs child can garner the therapist a huge amount of credibility from the outset of therapy.

The clinical implications of this long-term element are multi-faceted. Whether working with a couple or a married individual, being aware of this dynamic alone can open doors of therapeutic relationship and provide access to deep underlying emotion. For example, simply acknowledging the uncertain future for a couple with a special needs child can garner the therapist a huge amount of credibility from the outset of therapy.

Exploring the couple’s—or individual’s—attitudes about the long-term impacts on the marital relationship can easily begin to give the therapist clues regarding present day struggles and concerns. This can also assist in setting goals, as well as tailoring a treatment plan. Consider the issue of finances, for example. For the special needs marriage, the long-term impact regarding finances is exacerbated by the uncertainty of potential long-term care of an adult special needs child. The underlying emotions point to a myriad of questions including, but not limited to, will we have enough money to survive? What will retirement look like? And most importantly, will you still be here for me? In summary, acknowledging and exploring the long-term impacts of having a special needs child can help any therapist in exploring underlying emotions and expectations in the present, ultimately helping the special needs marriage succeed.

The short view: Sacrificing the important for the urgent

Someone once said that having a special needs child is like having a six-month-old baby indefinitely! The time and attention in the early days of typical childhood is taxing and exhausting. The time and energy required to care for the special needs child is never ending and cumulatively exhausting. Couple that with the demands of maintaining a relationship and the recipe for marital discord can easily emerge. Many couples with whom I have engaged report that their relationship is the first and easiest dynamic to be pushed aside in order to care for the unending needs of the special needs child. If neglected, these relationships can suffer grave consequences.

The therapist must understand the often-unspoken strain on one or both parents and the impact on the marital relationship. Many special needs families live in a constant state of hyper-vigilance in relation to the needs and behaviors of the special needs child. Typical children require a significant amount of time and attention. Introduce the dynamics of safety, impulse control, destructive behaviors, to name a few, and the vigilance required to manage the special needs child is not only increased, but also constant in some cases (Marshak & Prezant, 2017). Consider the neurological perspective: The typical rhythms of family life are somewhat predictable, and include elements of both stress and rest. The parasympathetic nervous system (empathy/higher level reasoning) can function normally making marital connection feasible and hopefully enjoyable. In the special needs family however, the constant engagement keeps the sympathetic nervous system (fight/flight/freeze) queued in a state of constant readiness, heightening an anxious state. Anxiety is counter-productive to emotional connection and with the added doses of cortisol dispersed into the system, relational connection becomes contraindicated. Many special needs families struggle to complete the most basic tasks of caring for self, caring for other children, and simply maintaining a home. Couples can easily find themselves exhausted, exasperated, and disconnected. Sadly, marital connection becomes akin to a luxury item. Some couples need education on resources to help them gain access to respite resources which would allow them the opportunity to find time and space to nurture the marital relationship. Others need tools on managing their anxiety and strategies to maintain connection with their spouse in the midst of the chaos. Again, the nature of the special needs diagnosis often drives the train on the levels of energy and time required to care for the child, as well as affecting the nature and level of marital connection.

The attachment view: Typical vs. specialized

One of my own personal observations, which represents the need for further research, is the impact a special needs child has on the attachment cycle. In any functioning marriage, the natural ebbs and flows of married life bring both conflict and repair. Consider this example, however, to understand the differences in impact. Bob and Mary have two typical children, a six-year-old boy, and a 10-year-old girl. Enter the conflict over a common issue. The 10-year-old is doing homework, not necessarily concerned with the normal conflict. The six-year-old cannot find a favorite toy and requests assistance finding the toy. Either parent assures the boy that “we’ll find the toy in a few minutes,” and asks that he play with a different toy or watch his favorite show while the parents talk to address the conflict. The typical six-year-old has the cognitive ability to process the information, the request and can, in congruence with proper and age-appropriate human development, comply with the request giving the parents time to discuss their conflict and attempt repair.

Now consider the same scenario but assign a diagnosis of moderate autism to the six-year-old boy. As the conflict unfolds and the boy requests help finding the toy, he does not necessarily comprehend or agree with the request to play with a different toy otherwise giving the parent’s time to repair their small conflict. The child’s insistence and/or tantrum, fueled by the diagnosis, shifts the energy from the conflict to the child with the realization that the child will not concede until his toy is found. There is an immediate and cumulative effect of this recurring scenario as one partner likely engages to assist the child, and the other disengages from the scenario altogether, focused on the frustration that “we never get to talk.” At a cursory glance, reason would suggest to deal with the child and return to the attempt to repair. The reality, however, is that this scenario repeats itself on any given day in the special needs marriage and is not quickly rectified, if at all. The attempt to repair is not only thwarted, but often trumped by a new conflict that ends with the same escalating result. Given the constant nature of parenting a special needs child, not to mention the vigilance to maintain parental readiness as aforementioned, the marital relationship can easily suffer (Larson, 2006). Conflicts however, in and of themselves are not what do the damage. The cumulative attachment injury occurs as repair is repeatedly delayed, and in some cases, avoided as the attachment pattern emerges with one or both partners recognizing that their attempts to connect and repair will otherwise be hijacked.

The scenarios are endless, but the risk of not navigating attachment repair has potentially detrimental consequences. The therapist that attunes to the realities and complexities of the special needs marriage will wisely recognize how new and altered attachment patterns have emerged in the special needs marriage, which will assist them in developing strategies and interventions that solidify connection and attachment repair. Caution must also be exercised in not vilifying the special needs child(ren) as well, either by the parents or the therapist!

The closing view

Recognizing the reality of the special needs marriage will help MFTs in connecting with and attuning to their clients. Exploring and understanding the impact of having a special needs child on the marriage is paramount to solidifying the therapeutic relationship. Keeping the short- and long-term perspectives in mind, as well as the impacts to attachment, MFTs can exponentially increase their effectiveness in working with the special needs marriage.

Brad Lee, MDiv, MS, LMFT, is an AAMFT Professional Member and holds the Clinical Fellow designation. Lee currently serves as the Command Chaplain, 311th Signal Command, U.S. Army, Fort Shafter, HI. He is an EdD student at Liberty University, focused on developing a clinical model to support what he calls the special needs marriage. Together with his wife of 30 years, Lori, the Lee’s have six children.

REFERENCES

Freedman, B., Luther, G., Zablotsky, B., & Stuart, E. (2011). Relationship status among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A population-based study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 539-548. doi:10.1007/s10803-011-1269-y.

Larson, E. (2006). Caregiving and autism: How does children’s propensity for routinization influence participation in family activities? OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 26(2) 69-79.

Marshak, L. E., & Prezant, F. P. (2017). Married with special needs children: A couple’s guide to keeping connected. Columbia, SC: Woodbine.

Other articles

Reflection On My Brother’s Death & The Blessing of Guilt:

For all who have had to say their goodbye to a loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic and have not been able to say “good-bye.”

Jeanne Thiele Reynolds, DMin

Profession and Practice

In the AAMFT Governance Policies (December 2019)—and on the AAMFT website—there is a Core Purpose statement of AAMFT that reads, “Recognizing that relationships are fundamental to the health and well-being of individuals, couples, families, and communities, AAMFT exists to advance the profession and the practice of marriage and family therapy.”

Shelley A. Hanson, MA