Understanding mental health in the workplace requires an exploration of the multilayered individual, familial, and environmental factors associated with well-being. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory on human development offers a holistic framework and identifies five levels of impact: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem (Bone, 2015; Smith et al., 2022). The microsystem, the most influential level, refers to personal domains and direct contact with the family or in the home environment.

The mesosystem consists of interactional or relationship nuances as well as work-life boundaries and rhythms. The exosystem involves settings, conditions, and policies. The macrosystem encompasses how cultural or societal matters affect development. The chronosystem includes aspects such as time, era, or family life cycle. Minimizing occupational and relational hazards across domains helps enhance employee well-being (Yeung & Johnston, 2016).

Consider these descriptions of levels and corresponding implications for mental health in the workplace. At the microsystem level, individual factors entail personal values, sense of self-awareness, coping skills, physical illness, and presence of mental health diagnosis and symptoms. In addition, skillset, job satisfaction, and personality characteristics pertinent to help-seeking and advocacy may also play a role. At the mesosystem level, management style and interactions with supervisors and colleagues affect employee wellbeing. Issues such as trust and respect come into play, as well as relational dynamics such as psychological safety, diversity, equity, and inclusion, sense of belonging, and recognition. Challenges at this level can result in toxic work environment, workplace bullying, and retention issues. At the exosystem level, environment, scheduling flexibility, autonomy, and opportunities for growth impact employee mental health. Even workspace design, lighting, décor, and other contextual elements influence motivation and mood. Management can function as a barrier or source of support depending on expectations involving roles, productivity, and workload. At the macrosystem level, company stability and the state of the economy trickle down to employee well-being. At the chronosystem level, lifestyle adjustments due to divorce, illness, or aging, family caregiver responsibilities, and societal factors such as war, political divisiveness, global warming, natural disasters, and epidemics/pandemic have lasting effects.

Social determinants of health

From a social justice standpoint, it is also essential to address how health inequities sabotage overall quality of life (Mental Health America, n.d.). The United States Department of Health and Human Services lists social determinants of health as economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, safe neighborhoods, transportation, safe environmental conditions, and access to nutritious food and fitness options (World Health Organization, 2022). As systemic therapists, we understand how barriers to healthy food, clean water/air, and affordable housing impact personal and family well-being. Consider this example: A manager demanding that a staff member stay at the office beyond their assigned shift may not realize the disparity in transportation (e.g., the individual would miss the last scheduled bus).

>>AAMFT QTAN Webinar – Sustainable Clinical Practice: Combating Compassion Fatigue

The ripple effects of working late may also intensify family stressors due to added burdens of time, finances, and extended childcare. This could also lead to another common source of work-family conflict related to the interplay of parents missing children’s activities due to work and/or work because of childhood illness (Grzywacz & Smith, 2016). Family dynamics can be both a source of strength and a stressor (Reimann, Schulz, Marx, & Lükemann, 2022). The authors contend that in addition to partnership status and quality, how families navigate division of labor, caregiver responsibilities, fiscal management, childhood behaviors, and life cycle adjustments impacts health and wellbeing. As MFTs working with couples and families, we can explore systemic factors relevant for both individual and relational well-being.

Systemic principles and barriers to wellness

A plethora of family therapy concepts apply to workplace wellness. Bateson’s contributions involve communication and information processing, as well as systems principles such as cybernetics, feedback, and double bind. His assertion that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts” stimulates curiosity about the interconnected, interdependent nature of employee mental health (Bateson, 2000). Cybernetics pertaining to the scope of this article refers to how feedback can be used to assess and attain individual and organizational wellness-related goals (Adkins &Premeaux, 2019).

Mental Health in the Workplace – online discussion. Hosted by National University’s Whole Person Center featuring Dr. Shay Thomas, LMFT.

Just as Bateson might suggest that individual imbalances in mindset, sleep, and diet/nutrition influence mental health, he might prompt consideration of how the recursive nature of organizational dynamics and workplace culture shape well-being. A double bind involves repeated, conflicting messages that create a paradox leaving the person feeling stuck and confused (Bateson, 2000). Consider the double bind of someone encouraged to use paid time off (PTO) who is hesitant due to the tendency to work when they are “off” and the inordinate number of emails and responsibilities faced upon return. Ponder the frustration of wanting to support the organization’s growth via innovation only to be met with responses from management that uphold the status quo or homeostasis, another foundational systemic principle. This is reminiscent of the mnemonic device offered to MFT students for remembering that negative feedback loops result in “no” change. Revisiting the concepts of exosystem and mesosystem, employee mental health and workplace wellness are at risk when we resist meaningful positive changes and uphold practices that perpetuate individual illness and a hostile work environment.

Mental health of underrepresented employees is negatively impacted when there are concerns with psychological safety and inclusion related to factors such as gender, race, age, sexuality, class, religion, and ability. Murthy (2022) noted that female health workers experience disproportionate levels of “burnout, depression, anxiety, insomnia, and occupational distress before and during the pandemic” (p. 16). As stated by Shell, Teodorescu, and Williams (2021), Black mental health therapists not only wrestle with their own race-related discrimination but also suffer from higher rates of burnout due to secondary traumatic stress associated with their clients’ presenting concerns. Employees with disabilities deal with bias and exclusion related to accessibility disparities (Murthy, 2022). Moreover, millennials and Generation Z, LGBTQ+, Black and Latinx employees experience more mental health symptoms than the rest of adult workers (Ingoglia, 2022).

Borrowing from Gadamer’s notion of praxis, or practice wisdom, applied to workplace wellness, we must address the reality of interdependence and the power of relationships and systems thinking. Focusing on prevention and celebrating diversity helps to reduce anxiety and depression correlated with racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and other forms of prejudice. Recent reports by the US Surgeon General proclaim that “we must shift burnout from a ‘me’ problem to a ‘we’ problem” (Murthy, 2022, p. 20) and echo our focus on community and connection:

“Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation has been an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health. Our relationships are a source of healing and well-being hiding in plain sight—one that can help us live healthier, more fulfilled, and more productive lives” (Murthy, 2023).

A plethora of family therapy concepts apply to workplace wellness.

Systemic principles and practices in the workplace

Systems principles apply in both clinical work and organizational consultation roles. Bowen’s concepts of triangulation and differentiation help clients understand the emotional process of adjusting to role shifts in family businesses, as well as mergers and changes in leadership (Cole, 2012). Providers in these settings support mental health by educating clients on complementarity (over/under-functioning) and coaching them on communication strategies such as avoiding reactivity and triangulation (Rosenberg, 2012). MFTs in corporate America encourage stakeholders to employ a team approach to exploring behavioral health solutions relevant for efficient business practices (Prohofsky, 2012). The growth of graduate program specializations further exemplifies how MFTs are suited to work at schools, with military families, and in medical settings to advocate for collaboration, systemic conflict resolution relevant for employee mental health, and workplace wellness (Rambo, West, Schooley, & Boyd, 2012).

Organizational and relational factors impacting employee well-being

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) lists impediments to employee well-being as discrimination, inequality, excessive workload, and job insecurity. Resulting in the “great resignation” phenomenon, heightened concerns with psychological safety, personal freedom, and priorities amplified post-pandemic employee burnout (Mcgroarty, 2022). The National Council for Mental Wellbeing highlights solutions to such problems as fostering an open environment for discussing challenges and needs, facilitating peer connections, and offering mental health first aid and resources.

According to Ingoglia (2022), “structural and organizational approaches to time management and stress reduction can help working adults better cope with burnout, anxiety and other challenges” (para. 2). A study of 140 MFTs revealed that clinicians feel powerless when they have little to no control over their workload, clientele, and approach (Chen et al., 2019); the authors challenge supervisors and agencies to promote self-care strategies, rotate hours/coverage, encourage use of paid leave to prevent burnout, and urge providers to attend conferences to bolster professional identity connections to combat isolation.

Emotional well-being of MFTs

Since change is inevitable, how can we facilitate positive feedback loops in our self-care practices, personal relationships, and workplace dynamics to support our mental health? Numerous factors impact the mental health of practitioners in various workplace settings. Clinicians in community agencies and nonprofit organizations face demands of billable hours (Chen et al., 2019). Private practitioners struggle with isolation and financial pressures (Rokach & Boulazreg, 2022). Those in academia juggle grading, mentoring, and committee responsibilities while attempting to live up to “publish or perish” expectations (Rosenberg & Pace, 2006). University faculty across disciplines contend with high turnover rates, pressure related to rank/promotion, attacks on academic freedom, and extra time needed to support the mental health of students (Abrams, 2024; Smith et al., 2022). Providers in healthcare face pressure to perform based on high productivity standards. All these circumstances, in addition to the risk of compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress, have implications for our mental health (Chen et al., 2019).

Since change is inevitable, how can we facilitate positive feedback loops in our self-care practices, personal relationships, and workplace dynamics to support our mental health? Numerous factors impact the mental health of practitioners in various workplace settings. Clinicians in community agencies and nonprofit organizations face demands of billable hours (Chen et al., 2019). Private practitioners struggle with isolation and financial pressures (Rokach & Boulazreg, 2022). Those in academia juggle grading, mentoring, and committee responsibilities while attempting to live up to “publish or perish” expectations (Rosenberg & Pace, 2006). University faculty across disciplines contend with high turnover rates, pressure related to rank/promotion, attacks on academic freedom, and extra time needed to support the mental health of students (Abrams, 2024; Smith et al., 2022). Providers in healthcare face pressure to perform based on high productivity standards. All these circumstances, in addition to the risk of compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress, have implications for our mental health (Chen et al., 2019).

—regular contact with and respect for nature are as much a part of the ideal human condition as a healthy diet, regular exercise, and a robust social network.

Rooted in Bateson’s ecological principles and akin to social determinants of health, Laszloffy and Davis (2019) remind MFTs to consider how self-of-the-therapist and environmental factors such as weather, pollution, and toxins impact our well-being by reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety, and chronic illness. They declare that “regular contact with and respect for nature are as much a part of the ideal human condition as a healthy diet, regular exercise, and a robust social network” (p. 2-3). The authors also recommend that therapists bring plants into the office, explore the feasibility of outdoor client sessions and clinical supervision, and assigning nature-based homework.

Situating myself in terms of personal coping strategies and resources, factors contributing to my own mental health include faith/spirituality, nature, Pilates, poetry, quality time with supportive family and friends, travel, participating in wellness retreats, and having my own therapist. During the workday, I access the workplace wellness tab on my computer which includes 2-5 minute guided meditations, breathing exercises, links to upbeat songs, and videos featuring brief stretches. In addition to peer consultation, I also frequently text friends and colleagues for a quick vent or laugh. In terms of workspace design, I have a large panel canvas on my wall of the beach and postings of inspirational quotes.

Systemic solutions to optimize mental health and foster workplace wellness

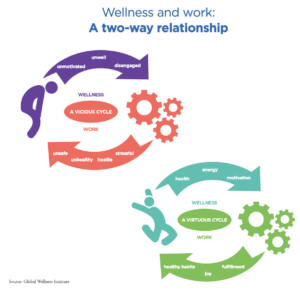

According to the Global Wellness Institute (Yeung & Johnston, 2016), workplace wellness initiatives refer to corporate policies and activities geared at optimizing employee wellbeing. It entails programs and incentives related to diet/nutrition, sleep, weight management, fitness, medical screening, and mental health services. Examples include employer-sponsored gym memberships, cooking classes, virtual wellness services, financial education classes, and health coaching programs. This author personally experimented with ways to mitigate physical ailments associated with vision problems, back/spinal issues, wrist and neck discomfort, and overall mobility concerns since the growth of telework during and after the pandemic. Companies invest in such programming primarily due to the correlation between employee health behaviors and employer healthcare savings.

Because burnout has become an occupational phenomenon, “caring for the carers” is a necessary focal point for workforce wellbeing (GWI, 2016; WHO, 2022). Recommended organizational programs and incentives include having a workplace wellness committee, promoting employee assistance program services, minimizing occupational hazards, reducing administrative burdens, encouraging volunteerism, and offering educational webinars such as smoking cessation, nutrition counseling, etc. (Ingoglia, 2022). The US Surgeon General (2023) also urges administrators to consider how policies for vacation and sick time, bereavement, and telework options impact employee well-being. Additional relational perspectives include addressing power and privilege, directly confronting discrimination and bias, forging community partnerships, investing in human-centered technology, and making mental health and substance abuse treatment accessible (Murthy, 2022). It is incumbent upon members of the entire system to be sensitive and responsive to how workplace expectations, policies, and relational dynamics mediate health outcomes and augment mental health.

Shatavia Alexander Thomas, DMFT, LMFT, is an AAMFT Professional member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations, a licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT), and a National Certified Counselor (NCC). She has worked in the mental health field for 20 years and in higher education for 10 years. Trained in family systems, her strengths-based style involves offering hope, maximizing resources, infusing creativity, and exploring the impact of language, cultural factors, and relationships. Thomas also maintains a small private practice.

Abrams, Z. (2024, January 1). Higher education is struggling. Psychologists are navigating its uncertain future. APA Monitor, 55 (1), 48.

Adkins, C. L., & Premeaux, S. F. (2019). A cybernetic model of work-life balance through time. Human Resource Management Review, 29(4), 100680.

Bateson, G. (2000). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago press.

Bone, K. D. (2015). The Bioecological Model: applications in holistic workplace well-being management. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 8(4), 256-271.

Chen, R., Austin, J. P., Sutton, J. P., Fussell, C., & Twiford, T. (2019). MFTs’ burnout prevention and coping: What can clinicians, supervisors, training programs, and agencies do? Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 30(3), 204-220.

Cole, P. (2012). Family therapy and family business. In Family therapy review: Contrasting contemporary models (pp. 253-255). Routledge.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Smith, A. M. (2016). Work-family conflict and health among working parents: Potential linkages for family science and social neuroscience. Family Relations, 65(1), 176-190.

Ingoglia, C. (2022, May 11). Fostering mental wellbeing in the workplace. National Council for Mental Wellbeing. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/fostering-mental-wellbeing-in-the-workplace/

Kissil, K., & Niño, A. (2017). Does the person‐of‐the‐therapist training (POTT) promote self‐care? Personal gains of MFT trainees following POTT: A retrospective thematic analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(3), 526-536.

Laszloffy, T. A., & Davis, S. D. (2019). Nurturing nature: Exploring ecological self‐of‐the‐therapist issues. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45(1), 176-185.

Mcgroarty, B. (2022, August 23). The future of workplace wellness: Meaning approaches, less spending on “programs.” Global Wellness Institute. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/global-wellness-institute-blog/2022/08/23/the-future-of-workplace-wellness-meaningful-approaches-less-spending-on-programs/

Murthy, V. (2022). The U.S. Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health & Well-Being. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/workplace-mental-health-well-being.pdf

Murthy, V. (2022). Addressing health worker burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory on building a thriving health workforce. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf

Murthy, V. (2023, May 3). New Surgeon General advisory raises alarm about the devastating impact of the epidemic of loneliness and isolation in the United States. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/05/03/new-surgeon-general-advisory-raises-alarm-about-devastating-impact-epidemic-loneliness-isolation-united-states.html

Prohofsky, J. A. (2012). Family therapy and corporate America. In Family therapy review: Contrasting contemporary models (pp. 259-261). Routledge.

Rambo, A., West, C., Schooley, A., & Boyd, T. V. (2012). Family therapy review. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Reimann, M., Schulz, F., Marx, C. K., & Lükemann, L. (2022). The family side of work-family conflict: A literature review of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Family Research, 34(4), 1010-1032.

Rokach, A., & Boulazreg, S. (2022). The COVID-19 era: How therapists can diminish burnout symptoms through self-care. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5660-5677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01149-6

Rosenberg, B. (2012). Practitioner’s Perspective: Intergenerational Models and Organizational Consulting. In Family therapy review: Contrasting contemporary models (pp. 76-78). Routledge.

Rosenberg, T., & Pace, M. (2006). Burnout among mental health professionals: Special considerations for the marriage and family therapist. Journal of marital and family therapy, 32(1), 87-99.

Shell, E. M., Teodorescu, D., & Williams, L. D. (2021). Investigating race-related stress, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress for Black mental health therapists. Journal of Black Psychology, 47(8), 669-694.

Smith, J. M., Smith, J., McLuckie, A., Szeto, A. C., Choate, P., Birks, L. K., … & Bright, K. S. (2022). Exploring mental health and well-being among university faculty members: A qualitative study. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 60(11), 17-25.

World Health Organization. (2022, March 16). Social determinants of health https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Yeung, O., & Johnston, K. (2016, January). The future of wellness at work. Global Wellness Institute. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/industry-research/the-future-of-wellness-at-work/

Other articles

A Systems Perspective on the Firefighter Mental Health Crisis

I spoke with John Nicoletti about the phenomenon of well-meaning but under-informed therapists. Nicoletti is best known for his work conducting debriefings after mass casualty events. He responded to the Columbine shooting in 1999 and the Aurora theatre shooting in 2012. He still does debriefings for law enforcement after potentially traumatic events. When I called him, he was sitting in his car about to head into a debriefing. Nicoletti told me that well-meaning therapists often show up after mass-casualty events but he has to turn them away because they have no experience. It’s not the kind of thing you can just “show up” to, like volunteering to hand out blankets and water bottles after a natural disaster.

Angela Nauss, MA

Why Therapists Need to Get Paid: An MFT Private Practitioner’s View

I would like to offer a candid, behind-the-scenes look at the way therapists get paid. As a marriage and family therapist who transitioned from a solo private practice to a group practice, I will highlight the unique challenges we face in getting paid and provide insight into the myths and limitations of our earnings. Like other professionals, therapists in private practice are compensated for their work, but only for the time spent with a client: our livelihood is directly tied to clients attending sessions.

Vanessa Bradden, MSMFT

From Exhaustion to Empowerment: A Therapist’s Guide to Supporting Clients Through Burnout

Maria, 34, comes into your office and slumps into the couch opposite you. She looks drained, and you notice that her outfit seems a little less put-together than usual. Something is clearly going on. She immediately dives into how “over work” she is, citing a micromanaging boss, unrealistic expectations, and no time off to speak of. A job that only five months ago had her brimming with joy has become a slog.

Megan Delp, MMFT