And here we are again. Ten years ago, Connecticut witnessed an unspeakable, violent tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, where 26 children and teachers were murdered with an AR-15 rifle. Since then, families in Newtown and across Connecticut have grappled with the aftermath of that trauma. One of Laundy’s MFT faculty colleagues at Central Connecticut State University at the time, also an AAMFT member, Nelba Marquez-Greene, is a mother in one of those families.

This unimaginable slaughter of elementary school children took place 13 years after the first widely-reported mass school shooting, the murder of 12 students and one teacher at Columbine High School in Colorado. Six years after Sandy Hook, on Valentine’s Day 2018, a graduate student in a family therapy class at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) suddenly began to scream. She had received a text from her younger brother, who was under fire from a gunman. Her brother survived, but 17 other students and teachers at Marjorie Douglas Stoneman High School in Parkland, Florida, near the NSU campus, did not. Faculty and students of NSU’s family therapy program, including Rambo, were immediately drawn into the aftermath. They have remained involved since then to keep programs for at-risk youth alive in the system (Rambo, Erolin, Beliard, & Almonte, 2019). As Laundy has stated, after a school shooting, first the candles, then the flames. While communities initially come together to grieve, a school shooting, like no other tragedy, breaks apart the assumed social contract and can lead to long-term community division (Rambo et al., 2019).

Alfaro is a doctoral student at NSU and became one of the family therapists hired by Florida school districts in the wake of the Parkland school shooting. Her job entails ongoing risk assessment, and her dissertation research involves teachers’ experiences of ongoing risk assessments. That research was interrupted in June 2022 by yet another school shooting (19 children and two teachers) at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas. Between Columbine and Uvalde, there have been 14 mass school shootings in the United States.

Why is this violence continuing to happen in US schools, and how can we best address it? This article seeks to offer context and recommendations regarding school violence for family therapists who practice in schools and the educational/healthcare teams with whom they collaborate. While mass school shootings are sadly familiar, distortion and confusion often follow in their aftermath. Let’s start by reviewing what we now know, after these many years.

What we know about school shootings

This is a United States problem

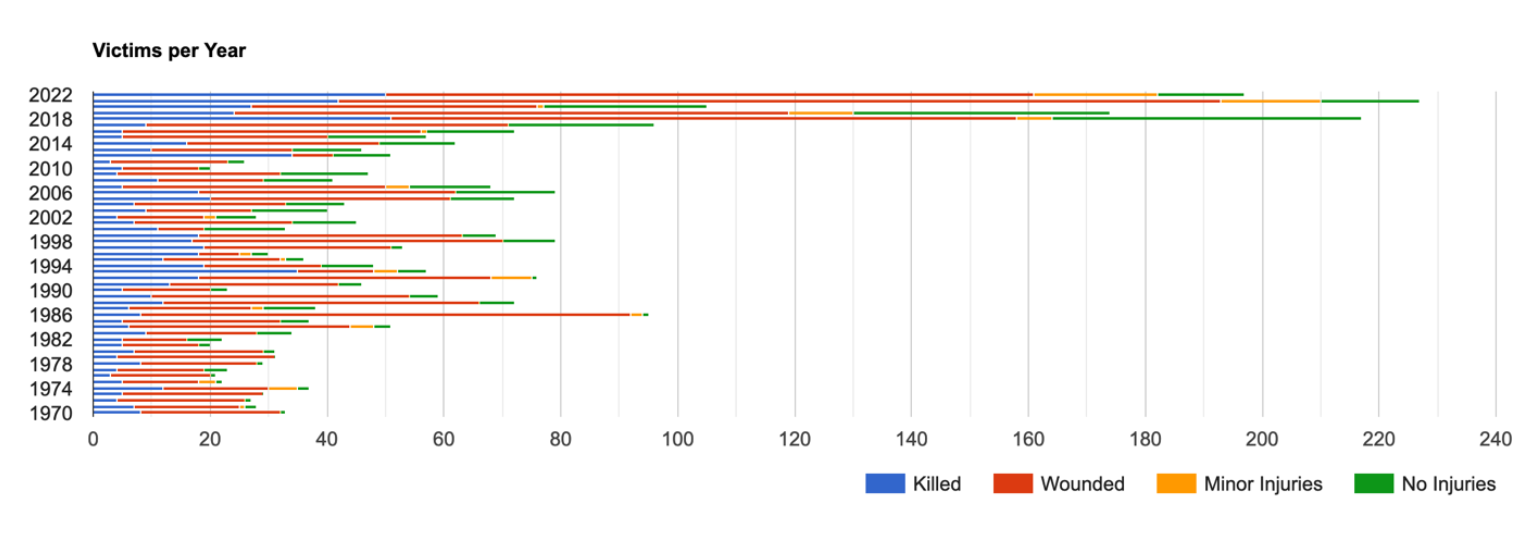

School shootings are at times defined as any incident of gunfire on a school campus, including for example a student shot by another student in an individual fight, and at other times limited to mass school shootings, defined as an intention to cause widespread and collective harm, resulting in the death of at least four people on the school campus, other than the perpetrator. By either measure, the U.S. stands alone. If we are counting school shootings of any type, resulting in death or injury to at least one person, between 2009 and 2018, the U.S. experienced 288 such incidents (World Population Review, 2022). The next largest number was Mexico, with eight, and Canada, with a comparable rate of private gun ownership, experienced two. If we count only mass school shootings, as defined above, between 2009 and 2018, the U.S. experienced 14 such mass casualty incidents; Canada experienced one, and Mexico had no school shootings that qualify (World Population Review, 2022). Of course, since 2018, the U.S. has experienced additional shootings. But the pattern is clear. There is something uniquely awful happening in the United States with school-based gun violence.

School shooters experience unhelpful group support

Websites promoting white nationalist and misogynistic views not only provide support for disturbed youth contemplating school shootings, they often provide active encouragement (Alfaro, 2022; Roose, 2019; Wells & Lovett, 2019). School shooters typically spend a significant amount of time on such websites (Langman, 2017). Most recently, the school shooter in the Robb Elementary School shooting identified with the “incel” movement (involuntary celibacy), as did the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas (MSD) school shooter (Lindsay, 2022). It is easy to imagine how the public would react if most school shooters were strongly allied, say, with websites affiliated with a particular minority faith or different nationality. But school shooters have received support from all too familiar racist and misogynist online groups, and the media persistently describes school shooters as “loners” (Metzl & McLeish, 2015). They are not just loners; vulnerable youth are affected by such misguided support and encouragement, including, for example, the avalanche of love letters sent to the convicted MSD school shooter (Bacon, 2018).

Disengaged parenting contributes, as does unsupervised access to guns

As systemic therapists, we know the importance of active and engaged parents. School shooters come from a wide variety of family backgrounds, but a common factor that has emerged is a lack of supervision, due to parental distraction, distance, or disengagement (Alfaro, 2022; Langman, 2017). To give just two examples, before the Columbine school shooting, the parents of one shooter discovered he had made a pipe bomb, yet they never searched his room or belongings, where he had an arsenal (Cullen, 2010). The Sandy Hook Elementary School shooter lived in the same house with his mother, yet communicated only by email (Sedensky III, 2013). Between 65 and 80 percent of school shooters obtain their guns from their homes or a family member (CDC, 2012). Parents may become disengaged in part because they are afraid; most school shooters have made repeated threats before acting, and some kill their parents (Alfaro, 2022).

Unsupported transitions contribute

School shootings tend to occur when the school shooter must make an abrupt transition from a smaller or more supportive school environment to a larger or less supportive one. These can include, for example, leaving special education for a mainstream program, or when the school shooter has been expelled, aged out, or otherwise removed from the school environment and forced to enter an adult life for which they are ill prepared (Baird, Roellke, & Zeifman, 2017). A day before the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, high school seniors from the gunman’s class from nearby Uvalde High School walked the halls of the elementary school in their graduation robes to inspire the young students. The gunman did not participate in the event but arrived the following day to kill; he was a high school dropout with little hope for his future (Beeferman & Douglas, 2022).

Further reading: Isolation and Disconnection

Why is this happening to us? Two perspectives

Projective identification

Laundy has found it useful to examine how we are coping with these challenges through the notion of defense mechanisms. The Encyclopedia Britannica (2010) defines Freud’s psychoanalytic notion of projection as a defense mechanism which displaces unwanted feelings onto another person when they appear as a threat from the external world. In clinical work, we address projection as the tendency to send outward and onto others those thoughts and emotions which are too painful to contain and process individually. Further, the notion of projective identification refers to the pattern of needing to continually project onto others that which is too complex, uncomfortable, and painful to contain and process internally. Psychotherapy seeks to help mature this tendency, to develop a wider range of more positive coping mechanisms to address internal discomfort.

It seems that in our current stressful environment, amid a pandemic, inflation, and many other stressors, we have elevated this defense mechanism into a national art form and pattern. It affects not only vulnerable youth, but all of us. At times, the current political and social milieu allows little room for collaborative discourse, and we are experiencing the dire consequences of that primitive coping mechanism. The result is too often anger and defensiveness among too many of us.

For at-risk students, and many others currently, projection and projective identification offer a primitive but dangerous antidote in the struggle to manage current life stressors and develop more mature and adaptive skills. The effects of such a primitive defense creates more distress rather than effective solutions.

A dominant discourse run amok?

Rambo anchors her understandings in narrative therapy and the concepts of dominant discourse and submerged voices. The United States’ addiction to the “myth of redemptive violence” (Wink, 1992), the idea that a bloodbath will eventually separate the good guys from the bad guys and allow good to triumph, is evident in our nationwide conversation about school shootings. Despite abundant evidence to the contrary, including this most recent school shooting in which 19 police officers waited outside for reinforcements during the shooting, a large number of Americans still believe more armed personnel, including armed teachers, would prevent school shootings (CBS, 2018). This focus has distracted us from efforts taken by other countries which have been more successful, and from common sense solutions we should be trying here.

What can we learn? What can we do?

Narrative therapy teaches us to look for unique outcomes; solution focused therapy teaches us to look for exceptions. It is easy to become overwhelmed by the horror and seeming inevitability of school shootings. Yet, shining examples of positive community building are right before us, and we can both learn from their example and join with them. After Sandy Hook, parents of murdered students faced unimaginable grief and every reason to despair. Parents nonetheless channeled their energies into constructive action, advocating for gun control, especially in cases of domestic violence and other at-risk situations, and early intervention in schools to reduce social isolation and add support. Sandy Hook Promise parents received death threats and were accused of faking their children’s deaths (BBC, 2018). Yet, they persevered.

After the MSD school shooting, teenage survivors formed their own organization, March for Our Lives. Sandy Hook Promise parents supported their marches and advocacy. March for Our Lives survivors focused initially on advocating for red flag gun laws, citing the tie between domestic violence and school shootings. Red flag gun laws allow police and other law enforcement to temporarily confiscate the weapons of those who have made credible threats or have been reported for domestic violence situations. At the time March for Our Lives began their advocacy, five states had such laws. After their initial push in 2018, the number increased to 19 states (Impelli, 2022), including Indiana and Florida, states traditionally hostile to gun control measures. In Florida alone, the red flag gun law has been used to confiscate weapons and prevent planned shootings 5,000 times. March for Our Lives teen survivors were derided as “crisis actors” and ridiculed by adult legislators. Yet, they persevered.

Finally, as this article is written, Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy and his committee’s Safer Communities Act has been enacted and signed into law—the first significant federal legislation to address school shootings in 30 years. Members of Sandy Hook Promise and March for Our Lives advocated strongly for this legislation, as did bereaved Uvalde parents. The new legislation is not perfect, nor is it likely to be enough. But it creates incentives for states to pass red flag gun laws, provides for increased background checks, and increases funding for mental health in schools, especially in the areas of early family intervention and support for transitions. As family therapists, we need to join with other healthcare providers and educators to stand beside bereaved parents and survivors as they advocate.

Learn more about the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act

The Russian novelist and philosopher Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1973) noted that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart—and through all human hearts” (p. 168). In vulnerable youth who are limited by negative and damaging life experiences and defenses, the attraction to negative power and violence cannot be underestimated. To address this challenge of helping such youth develop more adaptive and healthy coping skills, Margaret Mead recommended that we “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has” (Laundy, 2015, Introduction). Those words form a positive, systemic antidote to helping families and schools address the current challenge of youthful gun violence. Family therapists know well the systemic links between parental disengagement, online hate speech, and young people without roots or hope, coming of age in a culture where violence is too often seen as a solution. This is our time to act, collaborate with other healthcare providers, and support the affected families and survivors.

>>Kathleen Laundy is past president of AAMFT’s Family Therapists in Schools Topical Interest Network and Anne Rambo is the chair elect. They invite you to join in advocacy and to work with AAMFT to take a strong stand on these issues. https://networks.aamft.org/schools/home

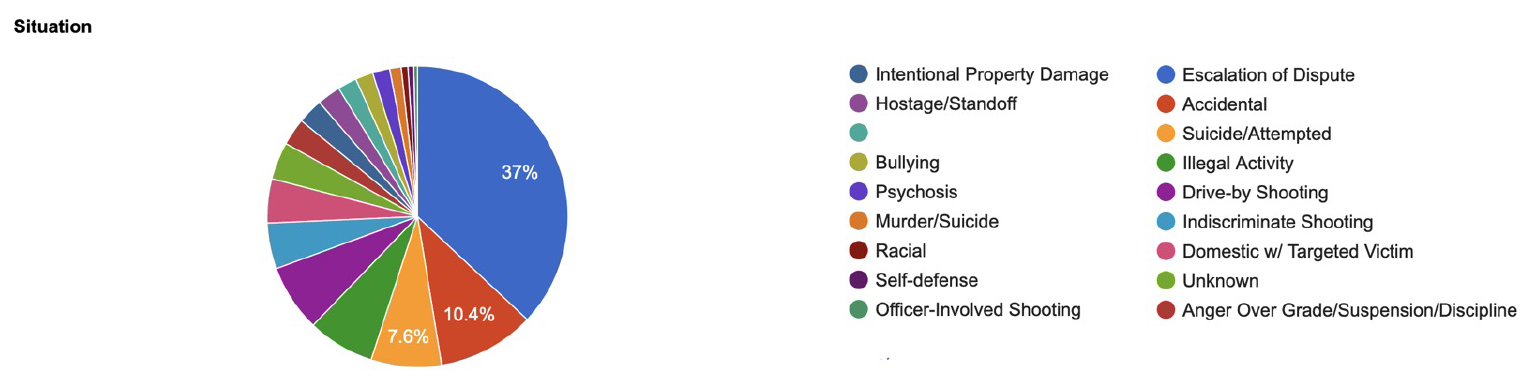

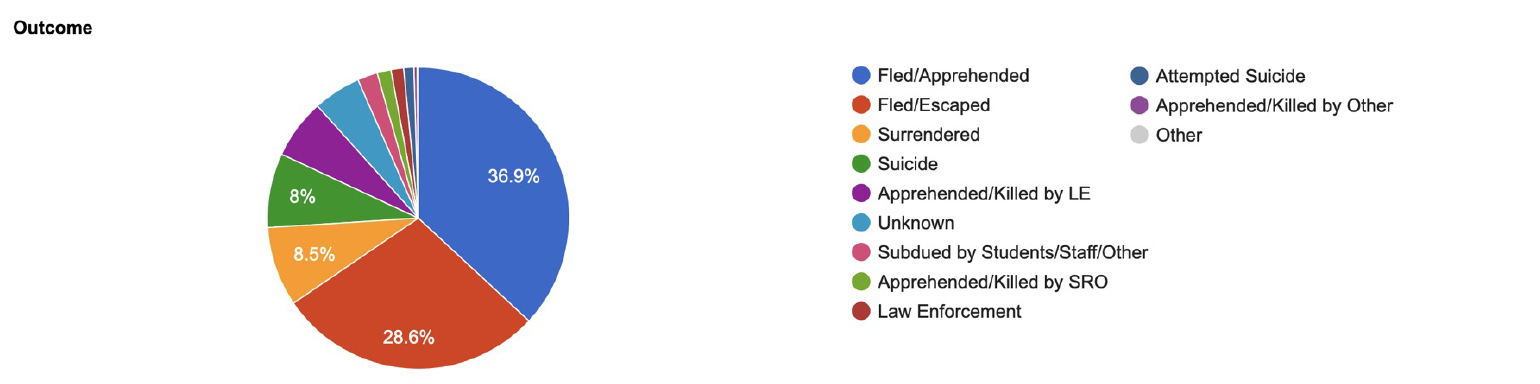

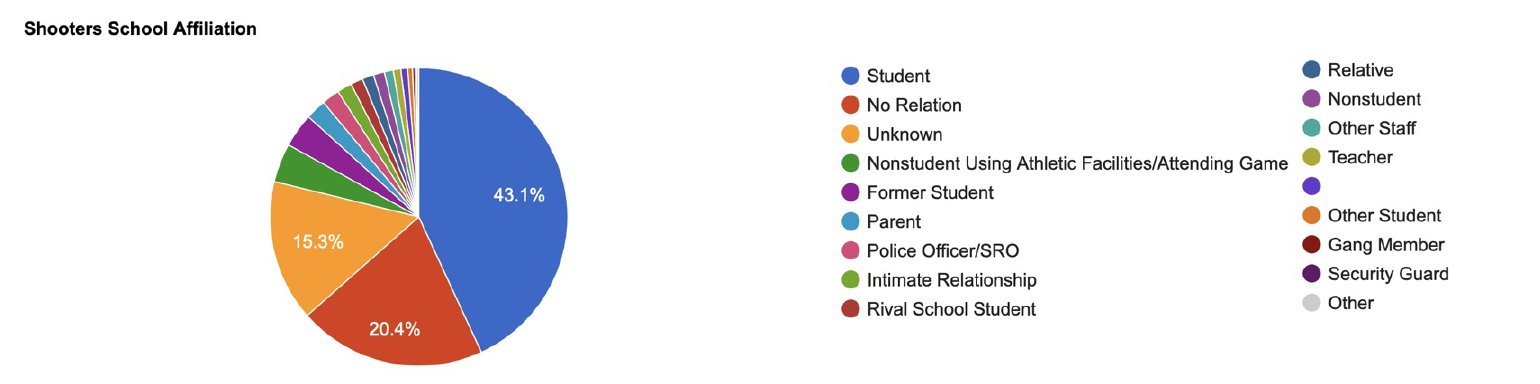

Data charts: Center for Homeland Defense and Security.

Kathleen C. Laundy, PsyD, is an AAMFT Professional Member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations. She is a clinical faculty member at the Counselor Education and Family Therapy Program at Central Connecticut State University where she has been a clinical professor for 15 years and has taught courses there in systems theory and psychopathology. Laundy has also served as a clinical professor at the Yale School of Medicine, where she has taught medical students about the family life cycle. She is also a featured speaker for AAMFT events, supporting the growth of collaborative, multidisciplinary healthcare. She consults with elementary, middle, and high schools across Connecticut to boost student achievement and help schools build multidisciplinary mental health teams to improve student and teacher resiliency.

Anne Rambo, PhD, an AAMFT Professional Member holding the Clinical Fellow and Approved Supervisor designations, has taught in the COAMFTE-accredited couple and family therapy program at Nova Southeastern University for three decades. She is currently program director for the MS in CFT program. She is a consultant to the Broward County school district and the chair elect of AAMFT’s Family Therapists in Schools Interest Network. For several years, her research and publication interests have centered around solution focused work with at risk youth and structures that sustain positive development for children and teenagers.

Alexandra Alfaro, MS, LMFT, is an AAMFT Professional Member holding the Clinical Fellow designation and a PhD Candidate at Nova Southeastern University. Her primary research focus has been school shooters for the last several years. She is a school-based family therapist, also working in private practice.

REFERENCES

Alfaro, A. (2022). Teachers and risk assessment: How well-intentioned training is perceived and understood. Unpublished dissertation: Nova Southeastern University.

Bacon, J. (2018, March 29). Nikolas Cruz fans send sexual pics, adoring letters to confessed killer. USA Today.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2018/03/29/nikolas-cruz-fans-send-provocative-photos-adoring-letters-confessed-killer/468750002/

Baird, A. A., Roellke, E. V., & Zeifman, D. M. (2017). Alone and adrift: The association between mass school shootings, school size, and student support. The Social Science Journal, 54(3), 261-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.01.009

BBC. (2018, April 17). Sandy Hook parents sue radio host Alex Jones for defamation.

BBC.com. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-43799449

Beeferman, J., & Douglas, E. (2022, May 25). A day after school shooting, Uvalde’s tight-knit community prays, donates blood and grieves. https://www.texastribune.org/2022/05/25/uvalde-texas-school-shooting-community/

CBS. (2018, February 23). Poll: Support for stricter gun laws rises; divisions on arming teachers. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/poll-support-for-stricter-gun-laws-rises-divisions-on-arming-teachers/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2012). Surveillance for violent deaths: National violent death reporting system, 16 states, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61, 1-43. http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/youthviolence/schoolviolence/SAVD.html

Cullen, D. (2010). Columbine. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2010). Encyclopedia Britannica. Chicago, IL: Author.

Impelli, M. (2022). Which states have ‘red flag’ gun laws in place? Newsweek. https://www.newsweek.com/which-states-have-red-flag-gun-laws-place-1710463

Langman, P. F. (2017). School shooters: Understanding high school, college, and adult perpetrators. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Laundy, K. C. (2015). Building school-based collaborative mental health teams: A systems approach to student achievement. Camp Hill, PA: TPI Press, The Practice Institute, LLC.

Lindsay, A. (2022). Swallowing the black pill: Involuntary celibates’ (incels) anti feminism within digital society. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 11(1), 210-224. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2138

Metzl, J. M., & MacLeish, K. T. (2015). Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 240-249. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302242

Rambo, A., Erolin, K., Beliard, C. A., & Almonte, F. (2019). Through the storm: How a master’s degree program in marriage and family therapy came to new understandings after surviving both a natural and a human disaster within 6 months. In L. L. Charlés & G. Samarasinghe (Eds.). Family systems and global humanitarian mental health: Approaches in the field (pp. 11-22). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Roose, K. (2019). ‘Shut the site down,’ says the creator of 8chan, a megaphone for gunmen. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/04/technology/8chan-shooting-manifesto.html

Sedensky III, S. J. (2013). Report of the state’s attorney for the judicial district of Danbury on the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and 36 Yogananda Street, Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012.

Solzhenitsyn, A. (1973). The gulag archipelago 1918-1956. HarperCollins.

Wells, G., & Lovett, I. (2019, September 4). ‘So, what’s his kill count?’: The toxic online world where mass shooters thrive. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/inside-the-toxic-online-world-where-mass-shooters-thrive-11567608631

Wink, W. (1992). Babylon revisited: How violent myths resurface today. Center for Media Literacy. https://www.medialit.org/reading-room/babylon-revisited-how-violent-myths-resurface-today

World Population Review. (2022). School shootings by country 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/school-shootings-by-country

Other articles

The Perils of Homelessness

On a daily basis, individuals who are homeless across the United States experience threats to their emotional, physical, and psychological well-being.

Sheldon A. Jacobs, PsyD

Intimate Partner Violence and Black Women

Many people have asked me, “What is intimate partner violence (IPV) and why is it important to me if I don’t specialize in treating it?” IPV is a social ill that includes, but is not limited to, physical violence, emotional violence, psychological violence, and sexual violence.

Lorin Kelly, PhD

Effects of IPV on Immigrant Latinas

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as domestic violence perpetuated by someone onto another person in an intimate relationship. IPV can take different forms, such as physical, verbal, sexual, or psychological abuse.

Jacqueline Florian, MA