Several years ago, before starting my journey as a marriage and family therapist (MFT), I found myself inside a preschool meeting room, seated across from a row of tense-faced women—a teacher, a psychologist, and the school director. They had a problem on their hands—an oddly precocious five-year-old boy who wouldn’t always cooperate, frequently talked back, and, most recently, had hit and kicked his teacher, boldly identifying her as, not only “mean,” but “stupid.” The boy was my son. As I faced this group, absorbing the imposing crime record, the image of “firing squad” came painfully to mind. The group was concerned. They prescribed therapy. I hardly knew what that meant or how it would help. My immediate goal was to escape that meeting as quickly as possible to collect and contain my overwhelming thoughts, emotions, and embarrassment.

Child disruptive behavior, commonly referred to by clinicians and researchers as externalizing behavior, is a significant problem in today’s schools. Externalizing behaviors are those with obvious visible manifestations, such as physical aggression, destroying property, fighting, or calling out disruptively (Liu, 2004). A longitudinal U.S. study of externalizing behavior in school (Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2010) identified 15% of the study population as showing either chronically high or steadily increasing externalizing behavior throughout elementary school. A 2019 U.S.-based study conducted by EAB, a best practices educational research firm, documented a notable increase in classroom disruptive behaviors, with surveyed educators reporting that almost 25% of their students exhibited disruptive behavior. Externalizing behavior within school systems demands attention, due to its adverse effects on the classroom environment (Krause et al., 2020; Silver et al., 2010). Further, child externalizing behavior draws societal and clinical attention, due to its association with future negative outcomes, including academic problems (Reid, Gonzalez, Nordness, Trout, & Epstein, 2004) and substance abuse, crime and violence, mental health struggles, and relationship problems into adulthood (Fergusson, Horwood, & Ridder, 2005).

Addressing parent shame and blame

The preschool made it clear that therapy was a condition of my son’s continued eligibility for their program, so we found a child therapist. I couldn’t believe I was the mother of a five-year-old in therapy. I wondered how we had failed. I wondered how a little boy surrounded by so much love could have so much anger. I was embarrassed when he acted out in public. I dreaded what people would think of us—the school, the neighbors… my parents. I began avoiding social events. I wondered what was wrong with my son and what it would mean for his future.

The parents (The term parent is used in this article to refer to all caregivers providing primary care to a child, including biological, adoptive, and foster parents; grandparents; legal guardians; etc.) of children with externalizing behavior find themselves in a statistical minority—that is, most children are not exhibiting disruptive behaviors at school. This distinction from the larger group can create a range of negative effects in the parent(s)’ experience, including feelings of blame, shame, guilt, self-doubt, stress, loss, and grief; parents may also feel misunderstood, judged, or socially isolated, or experience a perceived sense of incompetence or failure (Acri et al., 2019; Armstrong, Wilks, & Melville, 2003). Reinforcing the experience of blame and guilt is a strong societal belief, backed by research, which ties child conduct problems to parental incompetence and dysfunction (Armstrong et al., 2003; Mowat, 2015; Yan, Ansari, & Peng, 2020). Thus, the understanding of child behavioral problems is often simplified to direct linear causality from improper parenting (Mowat, 2015). Fewer numbers of studies address the etiology of behavior problems from a more complex and systemic perspective that considers inherent child characteristics; child-driven effects on parents; the transactional nature of child and parent behaviors on each other; and the effects of larger educational, political, and societal systems (Armstrong et al., 2003; Mowat, 2015; Yan et al., 2020).

As systemic therapists, we can help address the negative psychological impacts on parents, by providing psychoeducation on the etiology of child externalizing behavior, helping them understand that their child’s current behavioral manifestation may be due to biological factors (e.g., intense disposition or neurological differences), psychosocial factors (e.g., parenting style or traumatic events), or a complex interaction between these categories. A more complex understanding of causality can help parents avoid extreme views, either about themselves (“We’ve failed as parents”) or their child (“There is something terribly wrong with her, and she’s doomed”). In addition, we can provide basic psychoeducation about some common child diagnoses, such as ADHD and ASD, often associated with externalizing behavior.

Treating the whole family

I started worrying about my son’s self-esteem when he referred to himself as “the bad kid.” He even began speculating aloud whether he might “go to jail” someday. I was often aware that he was very unhappy about his reputation, but had no idea how to change it. I worried about my younger daughter, whom I sometimes found cowering under the stairs to escape her brother’s angry outbursts. It was wearying to receive constant phone calls from the elementary school feeling at a loss regarding how to create the needed change. My husband and I didn’t always agree on causes or solutions. The stress in our home was undeniable.

Treatment for a child with externalizing behavior often focuses on one of two extremes: isolating the child as the identified patient who needs “fixing,” or routing the parents to training. A more systemic approach that considers the needs and perspectives of all members of the family system, including interactional patterns among them, will do more to effect change and secure improved health for the entire family (Acri et al., 2019; Armstrong et al., 2003; Kratochwill, McDonald, Levin, Scalia, & Coover, 2009).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) offers one effective approach for conceptualizing and treating externalizing behavior in a family system. Harvey and Penzo (2009) provide an application of DBT for parents of children who need help regulating emotional outbursts and aggressive behaviors, as their approach adapts Linehan’s (Dimeff & Linehan, 2001) original DBT assumptions to parents and children; for example, you and your child “are doing the best you can,” “want to do things differently,” and “must learn new behaviors” (p. 32). The combined approach of accepting current situations, focusing on a desired future, and teaching more adaptive behaviors, provides an excellent framework to guide the therapist and parent with practical tools, including behavior management techniques and plans based in behavioral science.

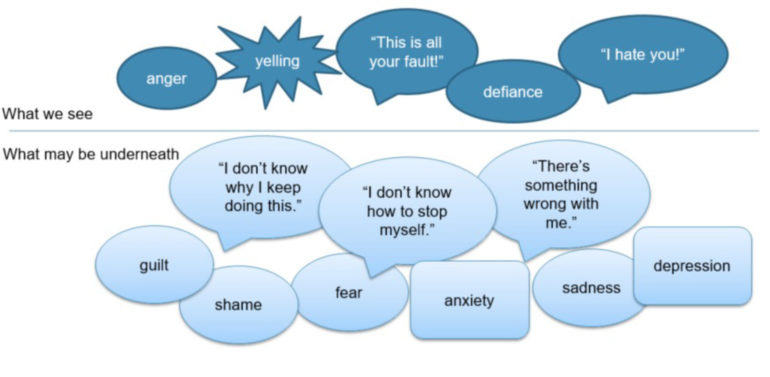

We can also assist clients in a host of practical ideas regarding care and support for the whole family: a) guide parents in healthy self-care practices for themselves and their couple partnership, if applicable, b) help parents understand that beneath a child’s outward aggression and defiance may be hidden feelings of guilt, shame, fear, or sadness (see Figure 1 below), c) guide parents in cultivating unconditional love and acceptance, positive interactions, and meaningful connection with their child, d) provide explicit guidance around safety, including the possibility of child self-harm, and e) be sure to address the effects of the family situation on siblings. Siblings of a child with extreme behaviors may compensate by trying to be perfect, may feel invisible, and may suffer from fear and confusion about their sibling—and they need validation, attention, and assurance from parents.

Figure 1

Helping families partner effectively with the school

I kept thinking and hoping that my son’s struggles were a passing phase that we’d eventually find an easy solution for. However, after many meetings, the school finally referred him for testing and evaluation for special education. The next meeting was attended by an army of school-based specialists, and one thumped a hefty legal document—“Your Family’s Special Education Rights”—onto the table. So many new terms—FAPE, IEP, IDEA, IEE. So many questions—“Would you like us to conduct the testing, or would you like to seek private testing that costs four thousand dollars?” We were being routed through an unfamiliar portal.

As systemic therapists, we also stand in the position to help families collaborate effectively with the child’s school. When externalizing behaviors occur in the school environment, teachers and staff may employ a variety of management responses, including verbal instruction, time-outs, removing privileges, physical restraint, seclusion, or sending the child to the principal’s office (EAB, 2019). If difficulties continue, the school may contact the child’s parent(s) to discuss possible causes and solutions. If school personnel believe there is reason to suspect a disability that may qualify the child for special education support, they may recommend testing to determine eligibility for an Individualized Education Program (IEP), a process that is guided by federal and state law. Though parents are mandated by law to be included in this process, if parents are unfamiliar with special education laws and jargon, they may feel like outsiders or observers, rather than contributors (Singh & Keese, 2020; Zagona, Miller, Kurth, & Love, 2019). The intention of special education law is to create a process whereby parents and school professionals contribute equally to understanding the child’s needs and collaborate on solutions; however, many parents feel marginalized and relegated to accepting solutions proposed by the academic experts (Singh & Keese, 2020; Zagona et al., 2019).

Regardless of whether a child qualifies for special education, research underscores the importance of parent involvement and positive parent-teacher partnerships in achieving the most successful outcomes for students (Fan & Chen, 2001). When addressing any type of school-based concern, the parent(s)’ unique understanding of the child adds a critical element in articulating the child’s needs and perspective in collaborating on solutions (Zagona et al., 2019). We can educate parents regarding their important role in collaborating with the school, and can encourage parents to seek out resources to educate themselves regarding school-based procedures, legal rights, terminology (including details about IEPs versus 504 plans), the intended role of the parent, and related options and supports. We can look into local public education resources for assisting parents and attend school meetings to help collaborate and advocate for the needs of the child and family.

Empowering the parent

Eventually, my son, the summer before second grade, was diagnosed on the autism spectrum and approved for special education at his school. It had been a three-year journey from that unhappy meeting at the preschool. The diagnostic clarity enriched our understanding of the struggles we had had and provided a pathway to effective help at school. Through therapy, books, and lots of in-the-trenches work, we learned how to understand our son and ourselves, how to relate in a loving and effective way, and how to structure our life and home so we could all thrive.

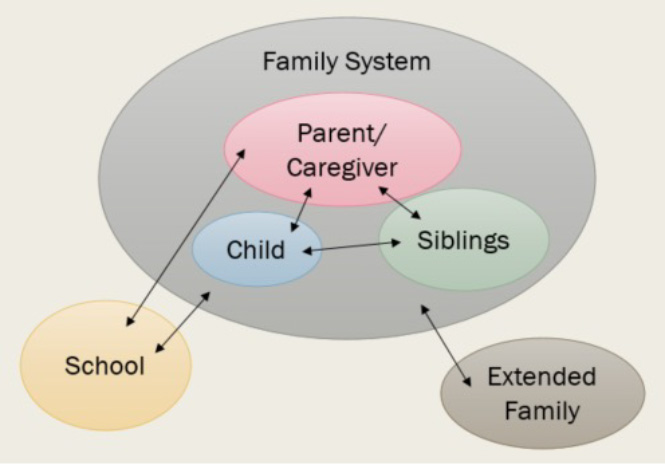

Regardless of the underlying cause of the behavior, a child exhibiting disruptive behavior in school is situated in a complex arrangement of intersecting systems. As systemically trained clinicians, family therapists are uniquely suited to consider and assess the multi-directional interactions occurring between the child and their parents(s), the child and their sibling(s), the parent(s) and the siblings, the child and the school, the family and the school, as well as the family and the extended family or community (see Figure 2). When working with such cases, one of our greatest contributions may be our ability to contemplate and address these multiple systems interactions. Our role may need to involve case management and continuously reassessing what exactly the family needs at a given point—family therapy sessions, parent coaching, in-home support for structuring space and routines, a psychologist for testing, a psychiatrist for medication consultation, an occupational therapist, parent support groups, group therapy for the child, books, podcasts, websites, etc.

Figure 2

As family therapists, we are ultimately interested in restoring a parent’s own sense of competence to address the needs of their child and family. At times, our systems assessment may counterintuitively involve the reduction of certain professional supports and the re-empowerment of the parent. As Roberta Gilbert, MD, of the Bowen Center noted (1999): “Parents are the hope of civilization. Much depends on whether parents can connect in a meaningful, positive way with each other and with their children” (p. 20). As MFTs, we hold the potential to exert influence in outward-radiating circles from parents, children, and families, to schools, communities, and beyond.

Marisa Beck, MS, is an AAMFT Professional Member, Resident in Marriage and Family Therapy, and works in private practice for Virginia Family Therapy in Falls Church, VA, under the supervision of Dr. Jeff Jackson, LMFT, and Matt Browning, LPC. She recently completed a clinical project as part of Virginia Tech’s MFT program. The project comprised an eight-hour interactive workshop for parents of elementary students exhibiting disruptive behavior problems at school. mbeck@virginiafamilytherapy.com Website

The author would like to thank Dr. Jeff Jackson, LMFT (Virginia Tech), Dr. Ashley Landers, LMFT (Ohio State University), and Sheri Mitschelen, LCSW, RPT/S (Owner & Director of Crossroads Family Counseling Center, President of The Heart Leaf Center, and Past-President of Virginia Association for Play Therapy) for their assistance in her recent clinical project and editorial comments for this article.

REFERENCES

Acri, M. C., Hamovitch, E. K., Lambert, K., Galler, M., Parchment, T. M., & Bornheimer, L. A. (2019). Perceived benefits of a multiple family group for children with behavior problems and their families. Social Work with Groups, 42(3), 197–212. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1080/01609513.2019.1567437

Armstrong, H. A., Wilks, C., & Melville, C. (2003). Clinical factors in group psychotherapy for parents of adolescents with disruptive behaviour disorders. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 15(1), 21–30. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1515/IJAMH.2003.15.1.21

Dimeff, L., & Linehan, M. M. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy in a nutshell. The California Psychologist, 34, 10-13.

EAB. (2019). Breaking bad behavior: The rise of classroom disruptions in early grades and how districts are responding. https://pages.eab.com/rs/732-GKV-655/images/BreakingBadBehaviorStudy.pdf

Fan, X. and Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13, 1, 1–22.

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Ridder, E. M. (2005). Show me the child at seven: The consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 46, 837–849. doi:10.1111/j.1469- 7610.2004.00387.x

Gilbert, R. (1999). Connecting with our children: Guiding principles for parents in a troubled world. John Wiley.

Harvey, P. & Penzo, J. A. (2009). Parenting a child who has intense emotions: Dialectical Behavior Therapy skills to help your child regulate emotional outbursts and aggressive behaviors. New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Kratochwill, T. R., McDonald, L., Levin, J. R., Scalia, P. A., & Coover, G. (2009). Families and schools together: An experimental study of multi-family support groups for children at risk. Journal of School Psychology, 47(4), 245–265. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1016/j.jsp.2009.03.001

Krause, A., Goldberg, B., D’Agostino, B., Klan, A., Rogers, M., Smith, J. D., Whitley, J., Hone, M., & McBrearty, N. (2020). The association between problematic school behaviours and social and emotional development in children seeking mental health treatment. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 25(3-4), 278-290. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1080/13632752.2020.1861852

Liu J. (2004). Childhood externalizing behavior: Theory and implications. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 17(3), 93-103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x

Mowat, J. G. (2015). ‘Inclusion—That word!’ Examining some of the tensions in supporting pupils experiencing social, emotional and behavioural difficulties/needs. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 20(2), 153-172. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1080/13632752.2014.927965

Reid, R., Gonzalez, J. E., Nordness, P. D., Trout, A., & Epstein, M. H. (2004). A meta-analysis of the academic status of students with emotional/behavioral disturbance. Journal of Special Education, 38, 130–143. doi:10.1177/00224669040380030101

Silver, R. B., Measelle, J. R., Armstrong, J. M., & Essex, M. J. (2010). The impact of parents, child care providers, teachers, and peers on early externalizing trajectories. Journal of School Psychology, 48(6), 555–583. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1016/j.jsp.2010.08.003

Singh, S., & Keese, J. (2020). Applying systems‐based thinking to build better IEP relationships: A case for relational coordination. Support for Learning. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1111/1467-9604.12315

Yan, N., Ansari, A., & Peng, P. (2020). Reconsidering the relation between parental functioning and child externalizing behaviors: A meta-analysis on child-driven effects. Journal of Family Psychology. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1037/fam0000805.supp (Supplemental)

Zagona, A. L., Miller, A. L., Kurth, J. A., & Love, H. R. (2019). Parent perspectives on special education services: How do schools implement team decisions? The School Community Journal, 29(2), 105-128.

Other articles

Systemic Perspectives on Perinatal Mental Health: Six Major Changes for Parents

Amy* was sitting slumped on a couch in my office for her initial appointment. She appeared a little nervous but was trying to hold it together. After pleasantries were exchanged, she stated she had her son four months ago, and since then, things had changed a lot around the house and with the family, especially with her in-laws. She explained she was feeling anxious, was short of breath, had overwhelming worries, and was irritable for the last couple of months.

Keiko Yoneyama-Sims, MS

AAMFT Foundation Awardee Spotlight

The AAMFT Foundation can improve outcomes by supporting the groundbreaking work of licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs). One of the ways we do this, is through our awards program. To support future awards, consider a charitable gift. Today, we are highlighting a past awardee: Aimee Hubbard, MS, PhD, PLMFT

Marriage and Family Therapist Workforce Study 2022

In the first half of 2022, AAMFT conducted an industry workforce study to examine the shifts related to COVID-19, their short- and longer-term impacts, and what challenges and opportunities are facing the field. In each issue of Family Therap-eNews, we examine a data point from this report.