Anti-fatness is a pervasive function of society. It dwells in the outermost layer of society’s systems and encroaches on each inner level, carefully harming everyone along the way. By the time people with larger bodies encounter explicit anti-fatness face-to-face, they have already accrued the brunt of implicit anti-fatness that has increased their marginalization. Thus, anti-fatness deteriorates people’s relationships with themselves and others, and weaves one belief through everyone’s mind: “I hate fatness.” Healthcare has an enduring history of reinforcing this damaging ideal. Medicine has recently introduced advancements in medications specifically geared toward weight loss, which have begun to grow in popularity.

And while the medical field has a critical role in the management of physiological and medical concerns, the deep-seated systemic oppression faced by people with larger bodies urges further intervention at systemic levels. As weight loss medications become increasingly available, systemic therapists must embrace their role in addressing anti-fatness to assist patients in accessing holistic health.

A physician’s perspective (Karlynn Sievers, MD)

Although it is well known that body weight is influenced by a complex interaction of genetics and lifestyle, society’s attitude toward people with larger bodies does not reflect this complexity. People with larger bodies are likely to experience bias in a multitude of ways, including in the media, in their interpersonal relationships, in educational and occupational settings, and, unfortunately, in healthcare settings (Puhl & Suh, 2015). This bias leads to worsening and unintended health outcomes, both in direct ways (through maladaptive eating behaviors, reluctance to participate in physical activity, and increases in cortisol that contribute to increased body fat) and in indirect ways (through increases in depression and anxiety, low self-esteem, and avoidance of the healthcare system) (Puhl & Heuer, 2012; Himmelstein et al., 2015). And while doctors trained in learn to manage weight through lifestyle interventions and medication management, they are often ill-equipped to deal with the stigma and bias that patients face. Additionally, when patients are constantly viewed by others as lazy, unmotivated, or without willpower, they may come to view themselves this way. This internal attitude can also contribute to difficulty setting and achieving goals surrounding changes in diet and exercise, creating a vicious cycle.

While weight loss medications can help patients modify their lifestyle to lose weight, they cannot deal with the repercussions of weight bias that lead to chronic stress and low self-esteem. This is where partnership between physicians and MFTs can help patients be more effective in health management, even when they are using weight loss medications. While the patient’s physician deals with medical and physiological factors, MFTs can help patients overcome impacts from weight stigma, thus truly optimizing their path towards better health.

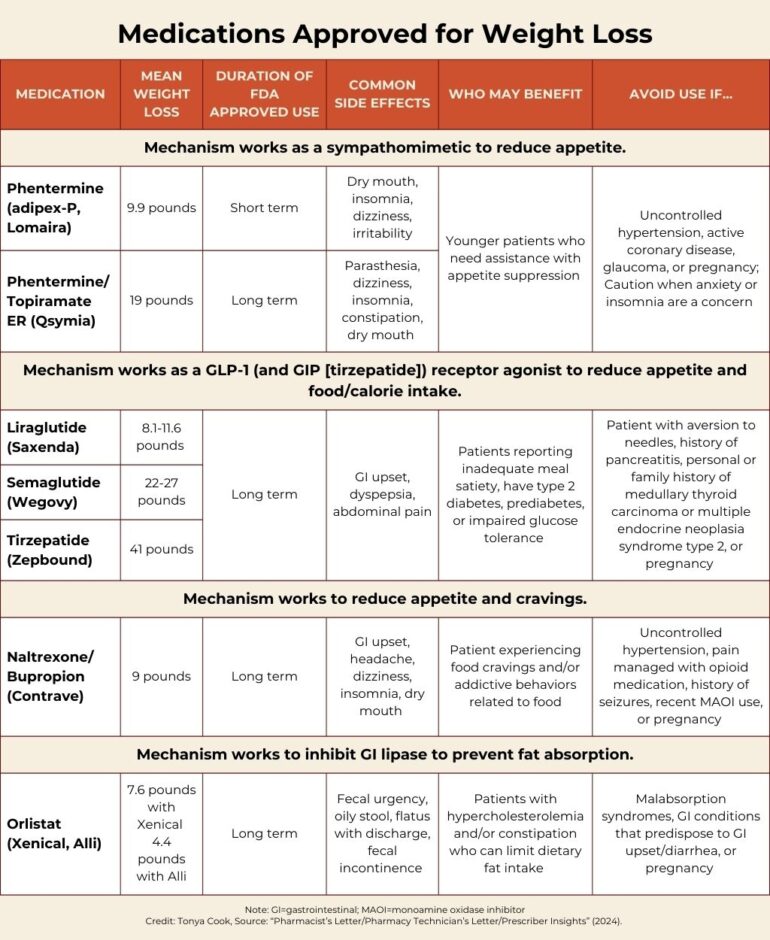

From a pharmacist (Tonya Cook, PharmD)

Medications for weight loss work in various ways to decrease appetite or increase satiety. They may be used for short-term (i.e., three months) or longer. Some newer evidence supports tapering weight loss medication to decrease the rebound weight gain that may occur when they are stopped (Seier et al., 2024).

Minding the gap

With the introduction of these medications, many may believe they have found a one-size-fits-all solution to their weight and health management. Unfortunately, these medications cannot address the socio-cultural systemic factors contributing to a person’s overall health. Whether MFTs work inside or outside of medical settings, they are specially trained and have a responsibility to address the systemic nature of a client’s concerns. In this case, the presenting problem is health inequity in the era of medication-assisted weight loss.

The Function of Anti-fatness

What history tells us. Manufactured from anti-blackness and racism, anti-fatness is the dangerous conflation that larger body weight is inversely tied to someone’s value, morals, status, and health. In reference to Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, Crane (2022) describes how the transatlantic slave trade established the falsehood that white people are superior and “fatness was considered a sign of immorality… as well as racial inferiority.” Years later, a measurement table now termed the body mass index (BMI) was created using only “white, cisgender European [men]” as subjects (Crane, 2022). In line with racism and ableism, the creator’s original purpose for this table was not to measure health or weight, but to determine the average or ideal man and establish any deviation from this image as unacceptable. Eventually, insurance companies accepted the BMI as a standard for measuring a person’s health status, and it continues to serve as a clinical measure today despite its faulty origins. Healthcare is but one major setting in which anti-fatness is presented and upheld, but the assumptions made therein feed systemic attitudes that trickle into individual perception. This creates a welcome environment for seemingly helpful and supposedly benign thought patterns, behaviors, and interactions to be avenues of oppression.

So … why does anti-fatness persist despite its racist foundation and the harm it causes?

- Non-Hispanic Black people had the highest prevalence of clinically measured larger body weight (i.e., BMI of 30 and above) among adults in recent years (Hales et al., 2020).

What does that have to do with anything?

- The populations that were most harmed by anti-fatness originally continue to be disproportionately harmed by it today.

And?

- If a system functions as it was created to function and primarily affects the marginalized, there is no general incentive to change it. That is why increasing awareness of the impact of anti-fatness and eliminating its power and systemic presence is vital in enacting widespread change.

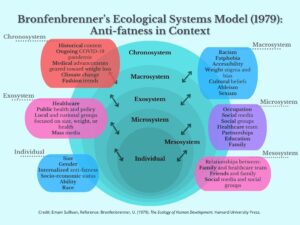

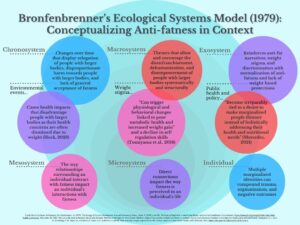

How is anti-fatness a systemic issue?

The presence and impact of anti-fatness exists at every level of society. Whether implicit or explicit, it can influence how an individual feels about themselves and how others and systems respond to them. And while it is harmful to everyone no matter their body size, it oppresses people with larger bodies disproportionately.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Filling the Gap

While every person has a role in addressing anti-fatness, MFTs are expressly qualified to acknowledge its function in clients’ lives due to their foundation in social justice and systemic thinking. MFTs can promote engagement in desired health behaviors while exploring the context that impacts an individual’s perception and experience of self, weight, and health. In the same breath, MFTs must first prioritize educating themselves on ways to reduce anti-fatness and internal weight bias and stigma.

- Listen to: Fat activists, personal experiences from people with larger bodies, and those negatively impacted by anti-fatness

- Take: Questionnaires to learn about implicit biases (e.g., Implicit Association Test [IAT], Antifat Attitudes Questionnaire [AFA], Fat Phobia Scale – short form, Universal Measure of Bias-Fat Scale [UMB-FAT], Weight Bias Internalization Scale [WBIS-M])

- Learn: Review Health At Every Size ® principles and Health At Every Size ® Framework of Care

Weight does not equal health.

Weight-focused interventions often support the assumption that body weight is equivalent to health. This mindset encourages the societal preference towards smaller body weight and the misrepresentation of fatness as unhealthy. Not only do these approaches limit maintenance of health-focused behaviors and appropriate assessment of disordered eating behaviors, but they also encourage harmful practices if people look healthy (i.e., thin) or are losing weight. Research has shown that people who participate in weight-focused interventions, like dieting, may lose weight, but they often regain it and have fewer overall improved health outcomes (Sole-Smith, 2020). Contrarily, for those who engage in counseling about body acceptance, [encouragement] to separate self-worth from their weight, and [education] about techniques for intuitive eating and strategies for finding physical activity they enjoyed… participants [report improvement to] their psychological wellbeing, physical stamina, and overall quality of life even though they did not lose weight. (Sole-Smith, 2020).

This supports other research that shows that “regardless of their weight class, people [live] longer when they [practice] healthy habits,” effectively dismissing body weight as the determining factor of health [ES1] [ES2] (Sole-Smith, 2020). The subsequent issue is that people’s ability to engage in healthy habits is systematically inequitable.

Medication-assisted health management through a systemic lens

When starting a weight loss medication, the intention is to simultaneously engage in behaviors geared toward desired health goals. At the beginning of treatment, there may be some ambivalence or difficulty finding motivation to begin desired health behaviors. The first step is helping clients shift their focus from weight-centric goals to health-centric goals. Biggs et al. (2021) found that intrinsic motivation was positively associated with engagement in desired health behaviors in accordance with self-determination theory. Interventions such as motivational interviewing or decisional balancing can increase motivation toward desired health goals.

- Offer: Education on how a medication may reduce [x] amount of weight (see Table 1) and explore realistic expectations

- Ask: “What do you enjoy about your current behaviors?”

- Ask: “What feels important to you about your health?”

- Ask: “How do you want your body to feel? What would you like your body to reasonably do?” (e.g., feel less fatigue, go on long walks with children)

- Visualize: Create a chart with the following questions: What are the benefits of engaging in desired health behaviors? What are the disadvantages of engaging in desired health behaviors? What are the benefits of not engaging in desired health behaviors? What are the disadvantages of not engaging in desired health behaviors?

Interventions should use ability-inclusive methods focused on increasing awareness, body acceptance, and value-based decision-making. Tools such as intuitive eating and SMART goals and therapy models incorporating mindfulness can be productive interventions.

- Explore: “What has worked for you in the past?”

- “How did that change your behavior?”

- “How did that make your body and mind feel?”

- “How did that impact your relationships with yourself, family, and friends?”

- Ask: “What values have guided you throughout life? What changes would you need to make to align closer with your values?”

- Explore: “How does your body feel when you perform (various types of movement)? How does your body feel when you eat (different foods)? How is your perception of your body changing?”[RR7] [ES8] [ES9]

- Do: Mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan, mindful eating, loving-kindness meditation)

- Offer: Actionable steps toward body acceptance (Gatewell Therapy Center, 2021)

- Explore socio-cultural factors impacting body image

- Support curating a body-inclusive social experience especially within media

- Encourage body neutrality through interventions prioritizing non-judgmental, mindful observation of thoughts about the self and body

- Encourage reduction of checking behaviors that increase body anxiety through redirection strategies

- Offer radical body acceptance practices adapted from dialectical behavior therapy

- Explore the body’s capabilities outside of appearance and aesthetics

- Explore values to encourage value-aligned behaviors

- Engage in experiential exercises to challenge current thought patterns (e.g., ‘as if’ technique)

- Educate about how weight does not equal health

- Offer body gratitude exercises

It is critical to assess any disordered eating and compulsive exercise behaviors or thought patterns before, during, and after individuals begin medication-assisted weight loss.

- Use: Screening and assessment tools (e.g., SCOFF, EDE-Q, EDE-Q, EAT-26, CET)

MFTs should ask about how the medication is impacting the client. This includes having an awareness of any side effects they may be experiencing (see Table 1) to offer validation about their experience and to encourage discussion with their primary care provider (PCP). In line with their scope of practice, it is important for MFTs to support prescribers but not adopt their responsibilities.

People can often feel disempowered when facing stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings. Thus, it is imperative that MFTs empower clients while also advocating for them in the ways they are able. This may include increasing clients’ self-advocacy skills or completing a release of information form to speak to their PCP. Collaboration between providers and clients is key to prioritizing holistic health.

- Ask: “What do you understand about why the doctor prescribed this medication?”

- Check in: “I’m aware of discriminatory encounters often experienced in healthcare settings, and I recognize your healthcare needs may require you to spend time in healthcare settings. I want to be sure our sessions can support you in that setting.”

- Offer: Encouragement to express their needs

- Write questions and thoughts down to bring up during appointments

- Have a support person on the phone or in person during appointments

- Cope early: Prepare coping skills for before, during, and after an appointment

- Practice: “Let’s talk through, plan, or role-play how you can show up in this conversation with your PCP.”

- Request before an ROI is obtained: “I want to support your overall health and what you’ve mentioned feels critical to that picture. How can I coordinate with your PCP that can help you feel supported?”

- Guide after ROI is obtained: “This feels important to your overall health. As we’ve already discussed, I would be happy to discuss this with your PCP so we can coordinate the next steps for your care. What are your thoughts about that?”

Weight loss is a goal on its own if desired, but if lost pounds are the only metric being measured as success, clinicians and clients are missing out on the opportunity to enhance holistic health. Here is a way to approach health management with medication that is person-centered and prioritizes reducing anti-fatness and weight bias and stigma.

Providers possess power as the culture setters of a clinical space and must cultivate a safe and accessible environment. A team of researchers have created a framework for the clinical space and staff to reference as practices transition to size-inclusivity (May, 2024) https://amihungry.com/articles/weight-inclusive-patient-care-practices/

The Association for Size Diversity and Health has also built a list of principles and a framework for healthcare professionals to increase size-inclusivity and reduce anti-fatness and weight bias and stigma (janzen et al., 2024)

https://asdah.org/haes/

Emani Sullivan, MS, is an AAMFT Professional member. She is an associate licensed marriage and family therapist in Illinois and holds an advanced specialization in medical family therapy. She received her Master of Science in marriage and family therapy from Northwestern University in Evanston, IL. She completed a medical family therapy internship at Intermountain Health St. Mary’s Regional Hospital Family Medicine Residency in Grand Junction, CO. She currently works as a therapist at Holistic Couple and Family Therapy in Chicago, IL. She acknowledges her privilege as a Black woman with a smaller body discussing anti-fatness. Please contact Emani to share any feedback or thoughts. esullivanne@gmail.com / www.linkedin.com/in/emani-sullivan

Karlynn Sievers, MD, is a board-certified physician in family medicine and obesity medicine. She completed her family medicine residency at Truman Medical Center – Lakewood in 2004, and became board certified in obesity medicine in 2022. She is the associate program director at St. Mary’s Family Medicine Residency program in Grand Junction, CO.

Tonya Cook, PharmD, completed her Doctor of Pharmacy training at the University of New Mexico in 2005. She then went on to finish an Ambulatory Care residency at the Asheville VA. At this time, Tonya is part of the faculty at the St. Mary’s Family Medicine Residency in Grand Junction, Colorado.

Biggs, B. K., Wilson, D. K., Quattlebaum, M., Kumar, S., Meek, A., & Jensen, T. B. (2021). Examination of weight-loss motivators and family factors in relation to weight management strategies and dietary behaviors among adolescents with obesity. Nutrients, 13(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051729

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Crane, M. (2022, April 13). The racist history of fatphobia and weight stigma. Within Health. https://withinhealth.com/learn/articles/the-racist-history-of-fatphobia-and-weight-stigma

Gatewell Therapy Center. (2021, October 2). Body acceptance practices – Stop hating your body today. Gatewell Therapy Center. https://gatewelltherapycenter.com/2020/05/05/body-acceptance-practices/

Hales, C. M., Carroll, M. D., Friar, C. D., & Ogden, C. L. (2020, February 27). Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm

Himmelstein, M. S., Incollingo Belsky, A. C., & Tomiyama, A. J. (2015). The weight of stigma: cortisol reactivity to manipulated weight stigma. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 23(2), 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20959

Hock, R. (2023, June 28). The risks of fatphobia to health and equity. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. https://www.ihi.org/insights/risks-fatphobia-health-and-equity

janzen, a., Austin, A., Garnett, V., Harrison, D., & Pilane, P. (2024, April 19). The Health At Every Size® (HAES®) Principles. Association for Size Diversity and Health. https://asdah.org/haes/

May, M. (2024, December). Weight inclusive patient care practices. Am I Hungry? https://amihungry.com/articles/weight-inclusive-patient-care-practices/

Mercedes, M. (2021, February 28). How to recenter equity and decenter thinness in the fight for food justice. Medium. https://marquisele.medium.com/how-to-recenter-equity-and-decenter-thinness-in-the-fight-for-food-justice-e364a895a6bf

Pharmacist’s Letter/Pharmacy Technician’s Letter/Prescriber Insights. (2024 Jan). Clinical Resource, Weight Loss Products [400103].

Puhl, R. M., & Heuer, C. A. (2012). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17(5), 941–964. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.636

Puhl, R. M., & Suh, Y. (2015). Health consequences of weight stigma: Implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Current Obesity Reports, 4(2), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z

Seier, S., Stamp Larsen, K., Pedersen, J., Biccler, J., & Gudbergsen, H. (2024). Tapering semaglutide to the most effective dose: Real-world evidence from a digital weight management programme (TAILGATE). Obesity Facts, 17(Suppl. 1), 449-449. https://doi.org/10.1159/000538577

Sole-Smith, V. (2020, July 1). What if doctors stopped prescribing weight loss? Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-if-doctors-stopped-prescribing-weight-loss/

Tomiyama, A. J., Carr, D., Granberg, E. M., Major, B., Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., & Brewis, A. (2018). How and why weight stigma drives the obesity ‘epidemic’ and harms health. BMC Medicine, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1116-5

Other articles

Reimagining Resistance: An Invitation for a Systemic Exploration in MFT Supervision

The construct of resistance is frequently discussed during marriage and family therapy (MFT), yet it is often addressed without being located in a systems-oriented framework. When therapists label clients or families as “being resistant,” we notice MFT supervision turning into an advice-driven environment where trainees invest a significant amount of energy in offering antidotes to the therapist who is plagued by the resistance itself. Although people are well-intentioned in their solution-oriented interactions, we believe that constructs that are rooted in a more traditional psychoanalytic approach might need to get a “systemic check” in order to be acknowledged when accounting for a systemic way of thinking.

Danna Abraham, PhD & Afarin Rajaei, PhD

Neuronutrition: An Introduction to an Important and Complex Topic

This new serial column on nutrition is for clinicians seeking more in-depth insights into the link between mental health and the body and the importance of understanding proper nutrition on the brain and emotional health.

Jerrod Brown, PhD, Bettye Sue Hennington, PhD, Tiffany Flaten, MEd, Jeremiah Schimp, PhD, & Jennifer Sweeton, PsyD

Embodiment & Equine Therapy: Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia Nervosa is a complex disorder. The diagnostic criteria as defined by the DSM-V is the “restriction of energy intake relative to requirements leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health; intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight; disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight” (American Psychological Association, 2013, pp.338-339). The incidence of diagnosed eating disorders is estimated to be 4.95% for women, and research indicates that one in eight women in the United States are impacted by subclinical disordered eating (Beccia, Dunlap, Hanes, Courneene & Zwickey, 2017).

Jennifer Cahill, MBA